Climate-Oriented Forest Management: New Guidelines for Massachusetts

2024 Report of the Massachusetts Climate Forestry Committee

Jump to page sections:

Introduction

David Foster, Director Emeritus, Harvard Forest, Harvard University

Background

Stephanie Cooper, Undersecretary for Environment, and Kurt Gaertner, Assistant Secretary for Environmental Policy, Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy & Environmental Affairs

Report of the Climate Forestry Committee: Recommendations for Climate-Oriented Forest Management Guidelines

Reflections on the Report by Committee Members

Richard Birdsey, Senior Scientist, Woodwell Climate Research Center, Woods Hole, Massachusetts

READ MORE →Alexandra Kosiba, Extension Assistant Professor of Forestry and Extension Forester, University of Vermont

READ MORE →Laura Marx, Climate Solutions Scientist, The Nature Conservancy in Massachusetts

READ MORE →Todd Ontl, Climate Adaptation Specialist, USDA Forest Service, Durham, New Hampshire

READ MORE →Christopher Riely, Licensed Forester & Conservationist, Sweet Birch Consulting, LLC, Rhode Island

READ MORE →Jennifer Shakun, Bioeconomy Initiative Director, New England Forestry Foundation

READ MORE →

Introduction

David Foster, Director Emeritus, Harvard Forest, Harvard University

Massachusetts supports the most carbon-dense forests in New England. Recognizing the important role of these forests and other natural solutions to climate change, Governor Maura Healey has committed to the permanent conservation of 40 percent of the state in forests to help achieve the goal of reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions in Massachusetts by 2050. To ensure that all forests in the state are managed in ways that support this climate goal, the Secretary of the Environment tasked a 12-person committee of individuals from Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island to develop a set of forest management guidelines. These guidelines and many other recommendations appear in the Report of the Massachusetts Climate Forestry Committee, which was released in early January 2024.

The editorial board of From the Ground Up recognizes the broad importance of this report’s recommendations to forests across New England. All six New England states are actively engaged in policy discussions on how forest management might evolve in the face of a changing climate. The analysis presented within this report may provide valuable insight for decision makers beyond the Massachusetts state line. We asked the lead individuals from the Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs to provide background on its genesis in relation to State efforts to address the crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. We also asked each of the 12 committee members to share their perspectives concerning the value of the report and aspects of its recommendations that are valuable to them individually. Half of the committee members accepted our invitation. These individuals represent the broad diversity of background and perspectives on the report, and we are grateful for their contributions, which are presented below.

The amount of carbon in the forests of New England varies tremendously, with extremely low values in the heavily cut industrial forests of northern Maine and the highest regional values in central and western Massachusetts. Figure courtesy of Brian Hall, Harvard Forest. Based on a figure from Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands and Communities: Broadening the Vision for New England. 2017.

As a member of the committee, I can underscore a few aspects of the committee process and report that are most striking to me. Of utmost importance was the open and collegial process, which imposed few constraints on topics or opinions. The report’s scope is consequently broad, encompassing the lands of all state agencies and including recommendations intended for application to private lands through education, training, and incentives. One notable hallmark of the report is the strong embrace of both passive management (for natural processes with minimal human intervention) and active management (purposeful interventions to promote specific outcomes). This integrated approach led to strong support for greatly increased land protection, for a large expansion in the number and area of reserves (wildlands) on public and private lands, and for concerted focus on climate-oriented ecological forestry. The report clearly articulates differences in opinion that emerged on numerous issues. Consequently, there is much to be embraced in both the process and the final report of this committee.

Background

Stephanie Cooper, Undersecretary for Environment, and Kurt Gaertner, Assistant Secretary for Environmental Policy, Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy & Environmental Affairs

In June 2023, the Healey-Driscoll Administration announced the Forests as Climate Solutions Initiative, a package of programs, financing, and actions designed to ensure that we are reflecting the latest science in our stewardship of public and private forests while accelerating land conservation efforts across the Commonwealth. This includes optimizing both carbon sequestration and storage, as well as improving resilience to climate impacts. To do this, we are focused on six key goals:

Reduce conversion (permanent removal of forests) and increase permanent protection of forests.

Enhance the alignment of forest management with climate goals.

Improve forestry practices in the woods and at the sawmill to support economic competitiveness and to reduce waste, energy use, and environmental impacts.

Increase utilization of harvested wood in long-lived products that sequester carbon.

Effectively integrate research and data into forest management.

Enhance the availability and accessibility of data on forests, forest management, and carbon sequestration.

Our elevated focus on forests recognizes that they cover nearly 60 percent of the Commonwealth and play a crucial role for people and the environment. In addition to providing clean air and water, serving as habitat for many species, and affording many other benefits, their ability to sequester and store carbon is critical to reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Forests as Climate Solutions deliberately seeks to advance the state’s Clean Energy and Climate Plan objectives and strategies for forests, most notably conserving 40 percent of the Commonwealth by 2050, expanding forest reserves, and incentivizing sustainable forest management practices.

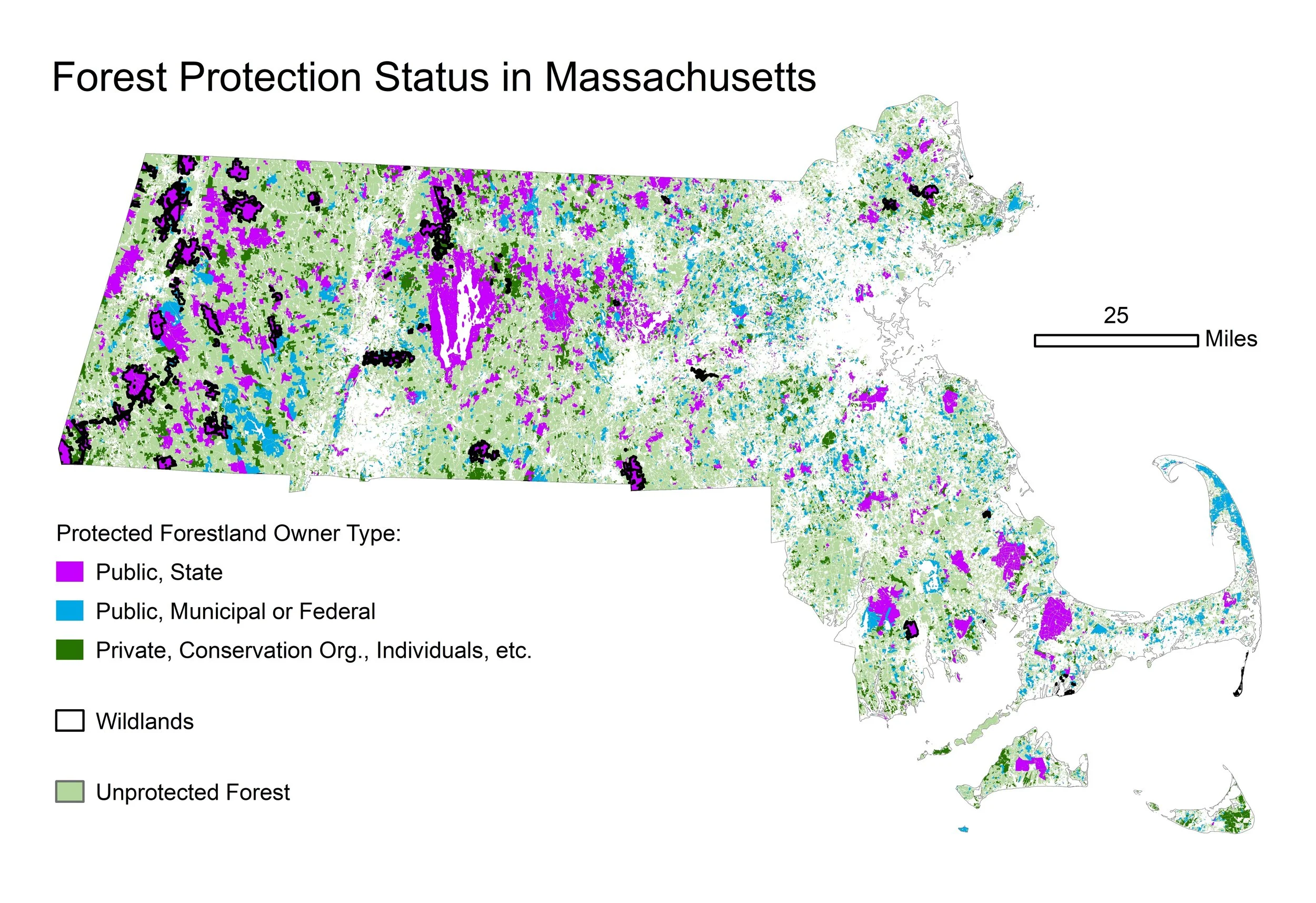

Forest Protection Status in Massachusetts. Map by Brian Hall, courtesy of Harvard Forest.

Climate Forestry Committee

As part of the Forests as Climate Solutions Initiative, the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) convened a group of 12 experts, known as the Climate Forestry Committee, to review current practices, and the latest climate science, with the charge of recommending a set of climate-oriented forest management guidelines for state lands. These lands are managed by the Department of Fish and Game’s Division of Fisheries & Wildlife and the Department of Conservation & Recreation’s Divisions of Water Supply Protection and State Parks & Recreation, and their dedicated staff. We set an ambitious six-month timeline for the Committee’s work, and during this time paused the execution of new contracts with private loggers for harvesting of timber on state lands. We are incredibly grateful to the members of the Climate Forestry Committee, who generously offered significant time and expertise over a short period of time. We deliberately selected a group of experts with a diversity of professional backgrounds and viewpoints, and were impressed by the collegial, thoughtful, and intentional approach they took to their charge.

Public engagement has also been an integral part of this process. Over the course of the six-month period that the Climate Forestry Committee was convened, EEA held two public meetings to inform the process. There were more than 200 attendees and nearly 50 oral commenters at each session, with more than 180 written comments received and subsequently made publicly available online. It was remarkable and inspiring to hear and read so many different views, ideas, and values about forests expressed in a thoughtful and respectful manner. Consistent with our commitment to engagement and transparency, we have also made the Committee’s recommendations available for public comment, to help guide the state’s consideration of them. As of this writing, the comment period is ongoing, and we look forward to reviewing comments while we continue to reflect on the Committee’s recommendations. We will provide a response to the recommendations and anticipate that implementation through agency land management will take a variety of forms, including updating of standards, protocols, procedures, manuals, and methods. We offer sincere thanks and appreciation to everyone who has participated in this process.

Report of the Climate Forestry Committee

The Climate Forestry Committee reviewed current science related to forests and climate change as a basis for its recommendations. Overall, the Committee’s recommendations are centered on land management approaches and forestry practices the state can employ to optimize carbon sequestration and maintain the significant carbon stocks in Massachusetts forests. The Committee concluded that forest management should take place on a continuum from passive to active, recognizing the complexity of forest landscapes, the unique circumstances of individual forest stands, the important influence of natural disturbances, and the diverse benefits forests offer society. At the same time, it urged state land managers to consciously embrace passive management — where natural cycles play out on the landscape and forests grow older and act as carbon sinks. In addition, the Committee offered a suite of recommendations to promote biodiversity, clean water, and resilience, while actively managing forests using silvicultural approaches. Some recommendations affirmed current practices for state lands, while others called for consideration of alternative approaches.

In addition to the more granular recommendations for management guidelines, the Climate Forestry Committee offered some broader suggestions for the state’s consideration. Among these concepts is following an integrated land management approach where goals are developed at a landscape scale, including considering state lands in the context of all forests in the Commonwealth. Similarly, the Committee supported expansion of forest reserves, calling for at least 10 percent of forests (of all ownerships) to be reserves, and urging permanent codification of reserves on state lands. It recommended that in doing so, the state consider the suitability of specific parcels for carbon storage, habitat, active forest management for wood production, and other benefits. Other recommendations the Committee advanced are demonstrating exemplary forestry practices on state lands; communicating clearly and accessibly about the rationale for and benefits of specific forestry projects; collecting more forest data using existing practices as well as new technologies; engaging in ongoing consultations with scientists to integrate the latest research into state lands management; and urging the state to allocate necessary resources to support all these efforts. The Committee also made recommendations pertaining to landowner and business incentives, such as incentivizing passive management and assisting with climate smart forest management plans for landowners, as well as supporting recruitment of more consulting foresters.

Members of the Climate Forestry Committee shared grave concerns about the known impacts and future threats of climate change on forests, and on the world. The Committee emphasized the essential priority of keeping forests as forests, and support for the state’s policies and programs that advance this goal. The Committee agreed that forests should be managed for a range of benefits, including but not exclusively for carbon sequestration and stocking. Further, the Committee noted that centering land management more directly on climate mitigation and adaptation will bring with it choices and tradeoffs. Where the Climate Forestry Committee did not reach consensus on a recommendation, it took care to articulate members’ different viewpoints and the related rationales. The Committee’s report is substantive, reasoned, practical, and ambitious, and offers much for the state and the public to ponder. Through consideration and incorporation of recommendations from the Committee and the public, we can steward our forest lands to help meet the challenges of climate change.

Forests as Climate Solutions Milestones

EEA is committing $50 million in initial funding to support the different “branches” and goals of Forests as Climate Solutions. Some of these funds will be used to expand our investments to support forest-based businesses, including an annual convening to share best practices, resources, and the latest science. For forest landowners, we are increasing financial assistance and providing expertise to apply climate-oriented management strategies to their lands. As part of our continued commitment to transparency, the State will launch a data dashboard displaying metrics regarding carbon storage and sequestration on state lands.

Supported by this investment, going forward we will focus on accelerating statewide conservation — in partnership with land trusts, communities, and landowners — to realize our critical Clean Energy and Climate Plan goals. We are excited about efforts to establish new forest reserves, dedicate more forest lands for conservation, and partner with private landowners to ensure that the forests of Massachusetts are perpetual, forever providing clean air, clean water, biodiversity, and the important climate protections we need to ensure a viable, sustainable future for the Commonwealth.

Reflections on the Report by Committee Members

Richard Birdsey, Senior Scientist, Woodwell Climate Research Center, Woods Hole, Massachusetts

The overarching goal of the Massachusetts Climate Forestry Committee was to “help the state ensure its forestry land management decisions are prioritizing climate mitigation and resilience, informed by the latest science.” The issues raised during the extensive discussions among the diverse committee membership went well beyond this mandate, largely because forests provide a myriad of services to society, and so prioritizing climate mitigation and resilience has broader impacts that were highlighted by some committee members. Although the committee was focused mostly on management of state forests, recommendations also have implications for management of private forests and their role in providing economic goods and other services.

Massachusetts forests store large amounts of carbon in biomass and soils, and are mostly in the 75 to 95-year-old age classes following historical abandonment of agricultural land. These middle-aged forests are generally in good health and could double their carbon stocks as they approach old-growth status at around 200 years of age. One of the main differences between ownership categories is that private forests are currently harvested about twice as frequently as public forests.

There is roughly twice as much forest area in private vs. public management, with state agencies managing 17 percent of the forest land. A little more than 10 percent of public forest land has some level of protection from logging. Overall, about eight percent of Massachusetts forests have some level of protection, according to U.S. Forest Service data.

Different perspectives from committee members about best approaches to manage forests to support state goals of reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions focused on either actively managing to improve resilience and faster carbon accumulation, or passively managing to allow natural processes to take place by protecting existing and future carbon stocks. The science underlying these two positions is that (1) younger forests can accumulate carbon faster than older forests while active management is needed to address disturbances, and (2) it is necessary to avoid emissions by protecting older forests that have significantly more carbon in larger trees while allowing natural processes to restore forests impacted by disturbances.

Faster carbon accumulation does not support a management approach involving harvest of mature and old-growth forests to create more area of younger forests, because of the significant emissions that occur during and after harvest, and throughout the processing, use, and disposal of wood products. On average, it would take about 100 years for a re-growing forest to replace the carbon emitted (also known as the “carbon debt”) from clearcut harvesting of a middle-aged forest. Therefore, in the timeframe of reducing net emissions by 2050 or 2100, it is strongly preferable to protect middle-aged forests and allow them to approach old-growth conditions, with large trees that are also more resistant to natural disturbances.

The committee noted the array of goods and services provided by healthy forests, establishing a broad context for the committee’s goal of increasing the emphasis on managing forests to help with the climate crisis. There was debate about the relative emphasis that should be placed on active vs. passive management, with active management aligning with the provision of economic goods from timber harvest, and passive management emphasizing increased protection for mature forests to support the public need for mitigating climate change. However, both active and passive management have roles to play, and it is necessary to take a landscape-scale view of forests, considering the relative merits of applying these two broad management approaches on private and public lands.

In Massachusetts, as well as nationally, almost all protected forests are in the public domain. This reflects the long history of designating protection of land for multiple public benefits, and selection of lands for protection that have unique characteristics or are needed for specific public goods, such as clean water or endangered species habitat. On the other hand, the many and diverse private landowners are more likely to own forest land for generating revenue from timber harvests or for recreation and hunting. These objectives lead to support for applying passive management approaches to public forest lands, and active management approaches to private forest lands. But since there is not enough state forest land to meet statewide protection goals even if all state forests were protected from logging, private lands should also be targeted for increased protection through incentive programs that provide options for landowners to avoid timber harvest.

It is important to acknowledge that these are not strict or universal mandates, but rather they need to be tailored to specific circumstances because of the diversity of ownership objectives, forest types, conditions, land use history, and natural disturbances that may increase in the future with climate change. This is where an informed public supported by knowledgeable forest managers will lead to the most appropriate mix of passive and active management on public and private lands respectively, to sustain timber production from private land while protecting areas on both public and private lands that can serve as strategic reserves for climate and other benefits.

Massachusetts forests are generally healthy and well stocked with trees, although data from the U.S. Forest Service indicates that 35 percent of public forests and 41 percent of private forests are less than fully stocked with live trees. If left alone, nature will eventually fill in these poorly stocked areas with additional trees that will both improve carbon accumulation rates and increase carbon stocks. Protecting public forests and allowing them to grow and adapt to future conditions, while employing active management of poorly stocked private forests, will help ensure a diverse mix of age classes statewide, and will benefit an array of forest services including timber, wildlife, biodiversity, recreation, and hunting. These targeted approaches would require legislative actions to increase protection of public forests, and incentive programs to foster better land management of private forests.

Alexandra Kosiba, Extension Assistant Professor of Forestry and Extension Forester, University of Vermont

As someone deeply engaged in forest ecology, climate change, carbon, and management — and as a Massachusetts native — I was honored to be asked to join the Massachusetts Climate Forestry Committee to aid in the development of recommendations for climate-oriented forest management on state lands. But I also recognized the challenge of this task. While it may seem intuitive to consider doing nothing as the optimal strategy for maximizing forest carbon benefits, this oversimplifies a complex and dynamic system in which we are intricately involved.

Recognizing climate change as a global atmospheric issue underscores the importance of understanding that our decisions have repercussions beyond our immediate surroundings. Through my work on forest carbon, I have become a stronger proponent of harvesting local wood products to reduce our reliance on resources sourced from distant locations. Currently, Massachusetts relies heavily on wood harvested outside the state. Although this approach may retain carbon within Massachusetts forests, it results in the same amount of carbon emissions to the atmosphere. Plus, the transportation of resources over longer distances contributes to increased greenhouse gas emissions. Importantly, outsourcing materials from elsewhere diminishes local oversight regarding impacts to the environment and the people that live there.

Embedded within the climate crisis is a call for more sustainable land use practices. In New England, there exists an opportunity to embrace local and sustainable resources, with state-managed forests showcasing exemplary planning and oversight in forestry operations. Similar to our approach to food, I advocate for fostering a passion for local wood products grown, harvested, and processed by our neighbors. The Committee’s identification of the primary threat posed by the loss of forest cover to other land uses emphasizes the significance of forests themselves, regardless of specific management actions.

While focusing on forests for their carbon benefits, I harbor concerns that we may overlook the fact that forests themselves are imperiled by climate change. Many New England forests, altered significantly by historical land clearing and exploitative logging, exhibit simplified structures; lack diversity in tree species and ages; and confront novel stressors such as invasive plants, insects, and diseases. Given this array of challenges, leaving every forest unmanaged may not be a wise stewardship decision for sustained long-term benefits.

I endorse an adaptive approach to forest management tailored to the unique conditions of each forest and addressing the needs of both nature and people. This involves a spectrum of management strategies, ranging from passive to active management, as detailed in the Climate Forestry Committee’s report. Thoughtful, well-planned, and ecologically based active management can positively impact forests by restoring ecological functioning, diversifying species composition, and enhancing complexity. Plus, doing so can provide a local source of resources, lessening our dependence on and impacts to other locations. While the challenges we face are immense, we have an opportunity to better recognize the interconnectedness of our decisions and the vital importance of conserving and managing forests for sustained benefits.

Laura Marx, Climate Solutions Scientist, The Nature Conservancy in Massachusetts

It wasn’t always this way, but today, nature is a part of nearly every substantive discussion of climate change. Climate change is caused by burning fossil fuels, and it must be primarily addressed through stopping that. Yet, because we’ve delayed meaningful action on emissions for nearly a half-century at this point, nature also has an essential role to play in cleaning up the carbon pollution already in the air. Trees and other plants do this at a lower cost and larger scale than any other tool currently available and are finally being recognized and valued for that role.

Forests: A Natural Solution to Climate Change. Courtesy of The Nature Conservancy in Massachusetts, 2021

Seeing this growing appreciation for the forests I’ve spent my career working to conserve is exciting, even when it comes with a side of controversy or confusion. The forest landowners I have the privilege to work with often start our conversations by saying something like: “I haven’t harvested my woods in 40 years,” or “I would really like to cut some trees in my woods.” This is usually followed by some version of “But I know that’s bad for the forest.” Both sets of landowners should take comfort in the recent release of the Climate Forestry Committee report by the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (with advice from me and 11 fellow scientists/forest professionals). The report reaffirms that both publicly owned and privately owned forests in Massachusetts benefit from a forest management strategy that includes passive (reserve/Wildland) and active (harvesting for wood and other values/Woodland) practices. The Nature Conservancy summed up these strategies in the graphic above.

The opportunity for respectful discussions with my colleagues, even in the few areas in which we disagree, was valuable. But this report was not without costs, including a pause on forest management while the report was written, and a distraction for already overworked state agency staff. The true measure of this work will be how it is translated into action. Already, the Healey-Driscoll administration has used the Climate Forestry Committee report to commit to: 1) provide additional funding and actions to protect forest land from conversion to development (which, on any given acre, is the best thing we can do from a forest carbon perspective); 2) quickly return to the thoughtful and well-planned forest management practiced by our state agencies; and 3) incentivize private landowners and forest professionals who choose climate-smart forest practices such as those in the Healthy Forests for our Future (TNC/USFS) guide referenced in the report. Like the report itself, these actions recognize the many essential benefits that our forests provide for us: carbon storage, clean air and water, wood, better health, shade, biodiversity, and the backdrop of some of our best experiences and memories.

Todd Ontl, Climate Adaptation Specialist, USDA Forest Service, Durham, New Hampshire

The Climate Forestry Committee was tasked with providing management guidelines that increase carbon storage and resilience to climate change on public lands in Massachusetts. This goal is fundamentally a question of how we, as stewards of these forests, optimize multiple goals that include carbon storage, climate resilience, and other benefits. While the discussions in this topic often focus on the goal of increasing carbon, the consideration of climate resilience is a fundamental first step in determining carbon management in forests.

Climate change is our current reality; 2023 was the hottest year on record both globally and in Massachusetts. Our recent past has shown us that destructive storms are increasing in intensity and frequency. In 2023 we saw the highest number of billion-dollar disasters in U.S. history. There is no doubt this record number of disasters was driven in large part by climate change and associated impacts. Heat and extreme weather are just the headlines of a longer list of climate change impacts affecting our forests in New England. These impacts can cause injury or death of trees, reducing the capacity for the forest to be a resilient carbon sink.

My input on the committee’s discussions was strongly in favor of recommending both active and passive strategies for managing forests to optimize carbon, resilience, and other benefits. As a scientist, I look to what the best science available says. That body of work tells us that forest stands that are healthy and resilient are places where passive approaches are most likely to provide effective carbon benefits. In places where climate risks are greatest, the capacity to absorb carbon from the atmosphere and the ability to store that carbon long term is at greatest risk of decline from tree mortality and forest health. The scientific evidence also suggests that there are management actions that can be employed to restore and maintain the health of our forests to foster resilience, with benefits to long-term carbon storage.

The assumption that if we let nature be, our forests will be fine, with the reality of the effects of climate change right in front of our eyes, is not consistent with the latest scientific assessments. This is especially true as I have understood, to a greater and greater degree as a forest ecologist, the profound changes to our forests as a result of over 300 years of human alterations.

In areas with greater resilience, low-intensity disturbances are most likely to have minimal impacts to carbon stocks, creating small gaps that add to dead wood carbon pools and create opportunities to recruit trees from the understory into the canopy. These gaps create stands of trees that sustain higher rates of carbon uptake through fast growth of young trees. The determination of a healthy and resilient forest stand needs to be an informed one — we need to apply data and analysis of forest conditions to arrive at the decision. But practical experience and peer-reviewed science supports that a passive management approach will not be effective for carbon mitigation benefits everywhere. Applying targeted actions in the right places is an effective strategy for forest carbon management.

Forestry practices applied in forests vulnerable to climate impacts can adapt these places to changing climate conditions, diversifying the composition of tree species and making them more complex.

This diversity is a hallmark of resilience, but often is lacking in many forests as they reestablished after pastures were abandoned a century ago. Many of these forests, composed of 80- to 100-year-old trees, often have few species, all of a single age class, nothing like the original forests the Indigenous people of the region knew, and the Europeans settled amongst. Importantly, more diverse forests have been shown time and again to not only be more resilient, but able to sustain higher carbon sequestration rates and carbon storage.

Active management practices that mimic those low-intensity disturbances that diversify forests, called “ecological forestry,” have as a primary purpose the goal of maintaining or enhancing the health of the forest, typically to the benefit of resilience and carbon balance as well.

One of the biggest challenges facing forest landowners, forestry practitioners, and policymakers is how to determine where forests are resilient and where they are at risk. If they are at risk, what is the most effective action to mitigate that risk to ensure a healthy and productive forest? These are the critical challenges the Climate Forestry Committee was tasked with providing recommendations to overcome for climate-informed carbon management on public lands in Massachusetts. The complexities of dynamic forest ecosystems and changing conditions makes these challenges formidable to overcome. I believe the committee provided actionable recommendations that enable Massachusetts to take steps towards addressing those challenges and help realize all the positive benefits of forests like water supply for our communities, recreation for our families, and nature to restore our spirits and enrich our lives.

At the end of the day, a healthy, resilient forest is our most effective natural climate solution. That forest is not necessarily the oldest forest or the one with the biggest trees. It is the one that has the best chance of being resilient in the face of the extreme changes in climate we are seeing today. That forest is the one that has the best chance at continuing to provide the benefits that we all know and enjoy today and the one that has the best chance to be enjoyed by our children and future generations.

Christopher Riely, Licensed Forester & Conservationist, Sweet Birch Consulting, LLC, Rhode Island

Being a member of the Climate Forestry Committee was a remarkable learning experience. When I saw the varied and robust list of members who had already signed on, I knew that it was an opportunity I could not pass up. When we started work, I found myself in the position of being one of the members with the most experience in planning and implementing forestry practices on the ground.

It is not often that I have been part of a group that has had so many passionate discussions about topics like natural disturbance, regeneration, and carbon storage. During these sessions, I often found myself considering conditions in specific forest stands I know well. How will the former stand of tall white pines blown down in a tornado this past summer likely rebound? Would the oak-dominated area of the state forest decimated by the spongy moth a few years ago benefit from intervention to benefit the diversity of the future canopy? How should I advise the owner of a hillside forest heavy to pest-susceptible hemlock who wants to do the right thing for the long term and needs periodic timber income?

Tornado Impacts, Summer 2023. © Christopher Riely

Clearly one of the take-home messages from the guidelines is that we need to emphasize an integrated approach to caring for state lands that includes both active (woodlands) and passive (wildlands) management areas. Both parts of this approach are important for Massachusetts to make progress toward achieving its big-picture climate goals. The committee admittedly had limited time to devote to the role of wood products in this equation, as it was beyond the scope of our work. I hope that this topic is receiving thoughtful consideration from those working on other parts of the Forests as Climate Solutions Initiative.

As one who is involved with research on actively managing for resiliency, I have a strong interest in testing different forest climate adaptation strategies and learning from how they work out. This can entail creating conditions intended to promote regeneration of young trees or favoring certain species that are projected to be better-adapted to changing climate conditions. We are learning that traditional conservation-minded forestry is often also climate-smart forestry. As to designating more wildlands, we know that there are already a lot of long-unmanaged stands on public lands that essentially already function as reserves. I think that many foresters will be supportive of identifying these areas if they are invited to participate in the process and share their knowledge of the land.

I believe the guidelines will help forest managers clarify and articulate their goals rather than muddling ecological, social, and economic outcomes together. This can inform how we evaluate the success of efforts to care for our forests, which will in turn move us further along the path toward truly science-based management.

Jennifer Shakun, Bioeconomy Initiative Director, New England Forestry Foundation

As I reflect on my experience with the Climate Forestry Committee and the implications of the final report released in early January, I feel encouraged. I am heartened by the degree to which forests are in the spotlight within the climate conversation. It’s commendable that the Healey-Driscoll administration chose to convene such a committee, as well as the broader Forests as Climate Solutions Initiative (of which the Climate Forestry Committee is only a part). And, importantly, funding and resources are being directed to help ensure many of the economic and environmental benefits of this initiative accrue locally.

The report does not have all the answers and it will not be the last word on this topic, but it is a step in the right direction. Two aspects of how the Climate Forestry Committee framed its deliberations provide a good foundation for how the guidelines might be implemented.

The first is recognition that there is no one-size-fits-all management approach that is appropriate on every acre of forestland. Potential management strategies fall along a continuum, from passive approaches where there is little human intervention to more active approaches that vary in terms of the type and intensity of activity. The report makes clear that actions across that whole spectrum can contribute to addressing climate change. There is a role for active forest management in helping deliver important outcomes, including influencing the resilience of our forests in a positive way and producing renewable materials locally, to name only two. This can complement, rather than compete with, the need for having largely untouched forest reserves on the landscape as well.

The second is the suggestion that climate change should be a consideration regardless of the management goal. Rather than treating climate as a separate, stand-alone issue, the recommendations encourage us to examine our typical management considerations and goals through a climate lens. That helps us determine how to achieve our desired outcomes (e.g., habitat creation, wood production) in the most climate-aligned way, and to understand if there are tradeoffs to carefully consider.

Climate change has rightly been described as a “wicked problem” — one marked by deep complexity, uncertainty, and interconnectedness in terms of the impacts and the solutions. Our discussions about forests and climate reflect this and are often similarly resistant to simple solutions. Sometimes overly emphasizing one ecosystem service (e.g., in-forest carbon storage) over another (e.g., wood production) can create tradeoffs with other climate goals or societal needs (e.g., using renewable materials with a lower carbon footprint). The Climate Forestry Committee wrestled with some of these complexities, and readers will see that reflected in the report. Ultimately, the recommendations should be a reminder that climate decisions require constant conversation between the best science and our values. But one thing we all agree on is the intrinsic value of forests and our appreciation for the myriad ways they sustain us ecologically, materially, economically, culturally, and spiritually.