Landscape Scale Wildlands in Northern New England Threatened by Friendly Fire

A Reader Response

Editors’ Note: We always welcome and encourage responses from our readers. The following piece is a response to the Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’ report, featured in Looking for Balance: Wildlands, Woodlands, and Wood Consumption from our Spring 2024 issue. Read other responses.

The Acadian Forest sustained Abenaki hunters and their ancestors for millennia. Thoreau was so inspired by the wild “mossy and moosey” landscape that he proposed the preservation of reserves decades before the establishment of the first national parks in the United States.

These lands have been relentlessly cut over and abused by the timber industry ever since Thoreau’s visit. Today, over 40 percent of the forest acreage controlled by paper companies and large non-industrial landowners in the twentieth century, and now hedge funds, endowments, and other bodies of global capital, are “degraded.”

The area marked in red indicates former paper company lands now owned by various absentee investors. They are undeveloped and, except for remote hunting and fishing camps, unoccupied. Credit: Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’

The preservation of Baxter State Park’s 225,000 acres, thanks to Wildlands philanthropy, and the establishment of the Green and White Mountain National Forests early in the twentieth century via federal legislation, instruct us: The instant absentee landowners sell off their degraded timberlands to public or private buyers, the forest lands begin to heal themselves.

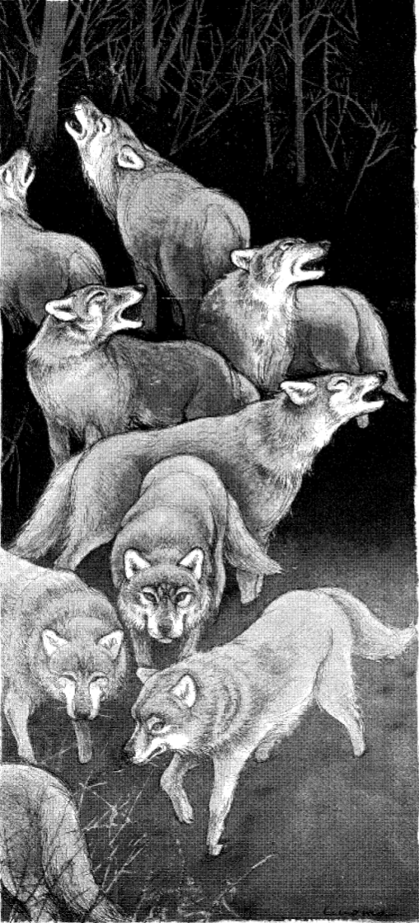

Attentive visitors to recovering forests may experience a hint of their former magnificence: lichen-clad snags, moss-covered dead wood on the forest floor; sounding mountain cataracts; springtime song of love-struck warblers, vireos, and kinglets—and perhaps ghost wolves.

“Thoreau was so inspired by the wild “mossy and moosey” landscape that he proposed the preservation of reserves decades before the establishment of the first national parks in the United States.”

Landscape-Scale Wildlands

In this age of climate crisis, the Sixth Extinction Event, and environmental injustice that has brought grief to humans and non-humans alike, we desperately need much larger, better-connected Wildlands, coupled with an end to land abuse on any parcel of land, whether a derelict city lot or a million-acre industrial forest holding.

Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future, published in 2023, profiled proposals, offered in the 1990s, for a 3.2 million acre Maine Woods National Park in the heart of the industrial forest and the Northern Forest Headwaters Wilderness Reserve System. The 2023 report, pages 91–92, observed:

“…the 8-million-plus acres of undeveloped and largely uninhabited former paper company lands of northern New England offer an unparalleled opportunity for rewilding vast expanses of land. The Acadian Forest region…encompasses entire landscapes capable of supporting the full range of natural disturbances and mosaics of ecosystems and could sustain the establishment of breeding populations of the region’s largest native predators.”

Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’

The authors of Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’ lay out the essential goals for protecting New England’s Wildlands and Woodlands: Protect forests; Reduce Consumption; and Expand Ecological Forestry. I hope these goals contribute to:

the establishment of a robust New England network of wildland reserves to preserve habitat for climate-stressed native species and to optimize the ability of forests to remove atmospheric carbon and store it long term;

the transformation of human behavior, especially a substantial reduction in demand for resources and energy, so that a low-carbon economy efficiently meets our basic needs; and

the development of a locally-controlled timber economy based on low-impact ecological forestry that sustains value-added wood manufacturing.

Beyond the Illusion makes a persuasive case for ridding northern New England of the absentee owners of its 12 million acres of severely degraded former industrial forest that produces most of New England’s forest carbon emissions. Profits on absentee-owned lands do not trickle down to the poor, rural timber communities. The current owners continue to overcut poorly stocked stands and eschew investment into long-term forest health. Working forest conservation easements on these lands, relying heavily on public funding, have failed to prevent overcutting or protect biodiversity and ecosystem integrity.

The Allagash River flows north. To the west (left), the dark green, 500-foot wide Allagash Wilderness Waterway beauty strip stands in stark contrast to the intensively logged-over corporate lands (left side of photo). The dark green (extreme lower left) is a portion of the Round Pond Maine Public Reserve. Credit: Google Earth Pro, 2013.

Nullifying the Dream of Landscape Scale Wildlands

To meet their arbitrary figure of active management on 20 million of New England’s 32 million acres of forest, the authors of Beyond the Illusion propose 11 million acres of these “corporate” forests for active management (see Table 2 on page 24). They offer no credible pathway to transforming global capital to plain citizen of the biota who will practice ecological forestry, thereby sacrificing fast profits for the sake of land health.

Beyond the Illusion acknowledges that “more holistic and long-term applications of ecological forestry practices…will likely require either greater consumer willingness to pay premiums for wood products or acquisition by other owners more inclined to adopt these values on their own.” The authors fail to discuss how past efforts to appease, subsidize, and bribe the owners to reduce cut have been expensive failures (see Lansky 1992 and Sayen 2023).

The illusion metaphor sets up an unintended, zero-sum game between Wildlands and Woodlands. David Publicover’s comments in the third issue of From the Ground Up, offer a clearer assessment of the challenge: “The vision set forth in the paper proposes an increase in the acreage devoted to both Wildlands and ecological forestry, a vision I wholeheartedly agree with… In promoting these transitions, we should recognize that there is more to be gained by transferring land into the desirable pools (Wildlands/natural areas and ecological forestry) than by transferring land between them. In northern New England, these transitions should primarily come from production forestry lands…. In southern New England, they should primarily come from the unmanaged forest pool.”

The 3.2 million-acre Maine Woods National Park proposal enjoys broad public support. Adoption of the approach of Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’ would nullify, for one or more generations, any hope for big rewilding east of the Rockies and the recovery of a value-adding timber economy in struggling timber-dependent communities of the region.

“In this age of climate crisis, the Sixth Extinction Event, and environmental injustice that has brought grief to humans and non-humans alike, we desperately need much larger, better-connected Wildlands, coupled with an end to land abuse on any parcel of land, whether a derelict city lot or a million-acre industrial forest holding.”

Aligning Human Desires with Planetary Limits

Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’ fails for the same reason most well-intentioned, anthropocentric conservation efforts fail: Even when it asks the necessary questions, it asks them in the wrong sequence. We must always ask these three questions in the following sequence:

Question 1: What are the needs of the land? Vast, unfragmented tracts of Wildlands provide ecological protections and services that cannot be replicated by smaller, more isolated reserves. Ending public subsidies to land exploiters would trigger large land sales. Redirecting counterproductive subsidies to acquire the former industrial forests, as these lands come on the market, would significantly mitigate climate change and habitat degradation. It is a sound investment.

Question 2: How do we transform the human behavior that is responsible for the climate, biodiversity, and environmental justice crises? We cannot change natural laws and limits, and when human aspirations conflict with natural limits, our only option is to change human behavior. The authors of Beyond the Illusion deserve high praise for their emphasis on demand reduction for wood products, energy, and unnecessary consumer products. Demand reduction is a pathway to a happier, simpler, more ethical life, and not some draconian ordeal.

Question 3: How do we meet basic human economic needs? Wildlands in New England (page 92) describes how the Headwaters proposal would transfer the focus of northern New England’s timber to the nearly 4 million acres of small woodlot owners on the periphery of the former industrial forest: “A vast Acadian Wildland would…benefit small woodlot owners in northern and central New England who have been trapped by global commodity markets that benefitted the largely absentee owners of immense tracts, but stifled the development of local, high-value-adding manufacturing opportunities… High-paying markets for quality sawlogs will reward smaller landowners for practicing low-impact forestry that emphasizes ecological benefits including carbon storage… They will be able to reduce their cutting and earn greater returns than were realized by selling pulp and chips.”

“Vast, unfragmented tracts of Wildlands provide ecological protections and services that cannot be replicated by smaller, more isolated reserves.”

Rather than kill Thoreau’s and his successors’ dream of rewilding, why not acquire these absentee-owned lands and restore them to the public commons?

Jamie Sayen is a longtime wildlands activist who lives in northern New Hampshire. He is author of Children of the Northern Forest: Wild New England’s History from Glaciers to Global Warming (2023) and You Had a Job for Life: Story of a Company Town (2017 and 2023).