Looking for Balance: Wildlands, Woodlands, and Wood Consumption

Morning Work on the Landing © Kathleen Kolb, Watercolor on Paper, 15” x 22”

Morning Work on the Landing

A poem by Verandah Porche

for Larry Sherman & Mark Sherman (1976-2013)

Dawn, the chickadees kick in.

Father and son are glad to be

Done with farming for nothing:

24/7 starving to death.

And zero ain’t so bad when

You’re dressed for it.The grapple holds aloft

A log longer than the man

Who felled it, snow on the bark.

The loader will never tuck this

One in the truck bed, and the son

Won’t snug it with his bar.Gazing back, the father grins:

This painting is right on the money:

The red hat, the blue cab,

The shadow they stand in

Between fell and grapple.Everyone’s life is a book, he adds.

What leaves his son won’t turn

Let’s overlook,

Like this valley or the empty

Mountain Dew not littering

The forest floor.

Reflections on a New Report, Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’

Jump to page sections:

Introduction

Perspectives on the ‘Illusion of Preservation’: Forests and Wood in New England

Caitlin Littlefield, Brian Donahue, Paul Catanzaro, David Foster, Anthony D’Amato, Kenneth Laustsen, and Brian HallReflections

Toward a Culture of Forestry Sustaining Forests

Michael Snyder, Licensed Forester and author of Woods Whys—An Exploration of Forests and Forestry, Greenfire Enterprises, Vermont

READ MORE →Forest Time

Lincoln Fish, Consulting Forester, Bay State Forestry Service, Athol, Massachusetts

READ MORE →Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’: Connecting People with Forests and Forest Products

Julie Renaud Evans, Program Director, Northern Forest Center

READ MORE →Wildlands Should Not Compete with Ecological Forestry

David Publicover, Senior Staff Scientist (retired), Appalachian Mountain Club

READ MORE →

Resolution

The Resolution of Preservation and Management

Brian Donahue, David Foster, and Caitlin Littlefield

READ MORE →

IntroductionPerspectives on the ‘Illusion of Preservation’: Forests and Wood in New England

Reflections on a New Report, Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’

Caitlin Littlefield, Brian Donahue, Paul Catanzaro, David Foster, Anthony D’Amato, Kenneth Laustsen, and Brian Hall

In 2002, Harvard Forest published The Illusion of Preservation, which captured the paradox that, in Massachusetts, the citizens’ pride in conservation contrasts with the fact that almost none of the wood products consumed in the Commonwealth are produced there. The new report, Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’, expands on that earlier report with a look at the entire New England region, framed by more recent research and conservation thinking on the part of Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities. The following is a summary of the report. Listen to this webinar by Caitlin, Paul, and Anthony (Tony) describing the findings.

The forests of New England support humans and non-humans alike in countless ways, as they have for thousands of years. It is therefore heartening to see a growing recognition of the importance of forests, as the planet warms, as species disappear, and as our connections with nature and with one another fray. We increasingly look to our forests as a “natural climate solution” and as inextricably linked with protecting biodiversity.

Watershed, Summer Morning © Kathleen Kolb, Oil on Linen, 36” x 54”

At the same time, wood from our forests also remains a valuable renewable resource we all rely upon and a key component of an emerging bioeconomy that can help mitigate climate change. And so, while pursuing goals to preserve more wild forests—which we, the authors, wholeheartedly support—we must just as steadfastly protect productive forests and seek to improve the standard of that production, right here in our own backyard. Despite covering 80 percent of the region, only a quarter of our forests are formally protected today; the rest lie vulnerable to fragmentation and development.

“Despite covering 80 percent of the region, only a quarter of our forests are formally protected today; the rest lie vulnerable to fragmentation and development.”

Even as the region touts a strong conservation ethic, we suffer from a considerable shortfall in production compared to our enormously high rates of consumption and our capacity for sustainable production. We meet much of that demand with wood drawn from places with weaker environmental and social oversight than exists in much of New England. These hidden costs are all too easy to ignore and will only be exacerbated if harvesting is reduced in New England while we maintain our present rates of consumption. Moreover, within New England, overly restrained harvesting in the south contrasts with, in many cases, overly heavy cutting in the north. Therein lies the Illusion of Preservation.

Courtesy of MassWoods, from Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’

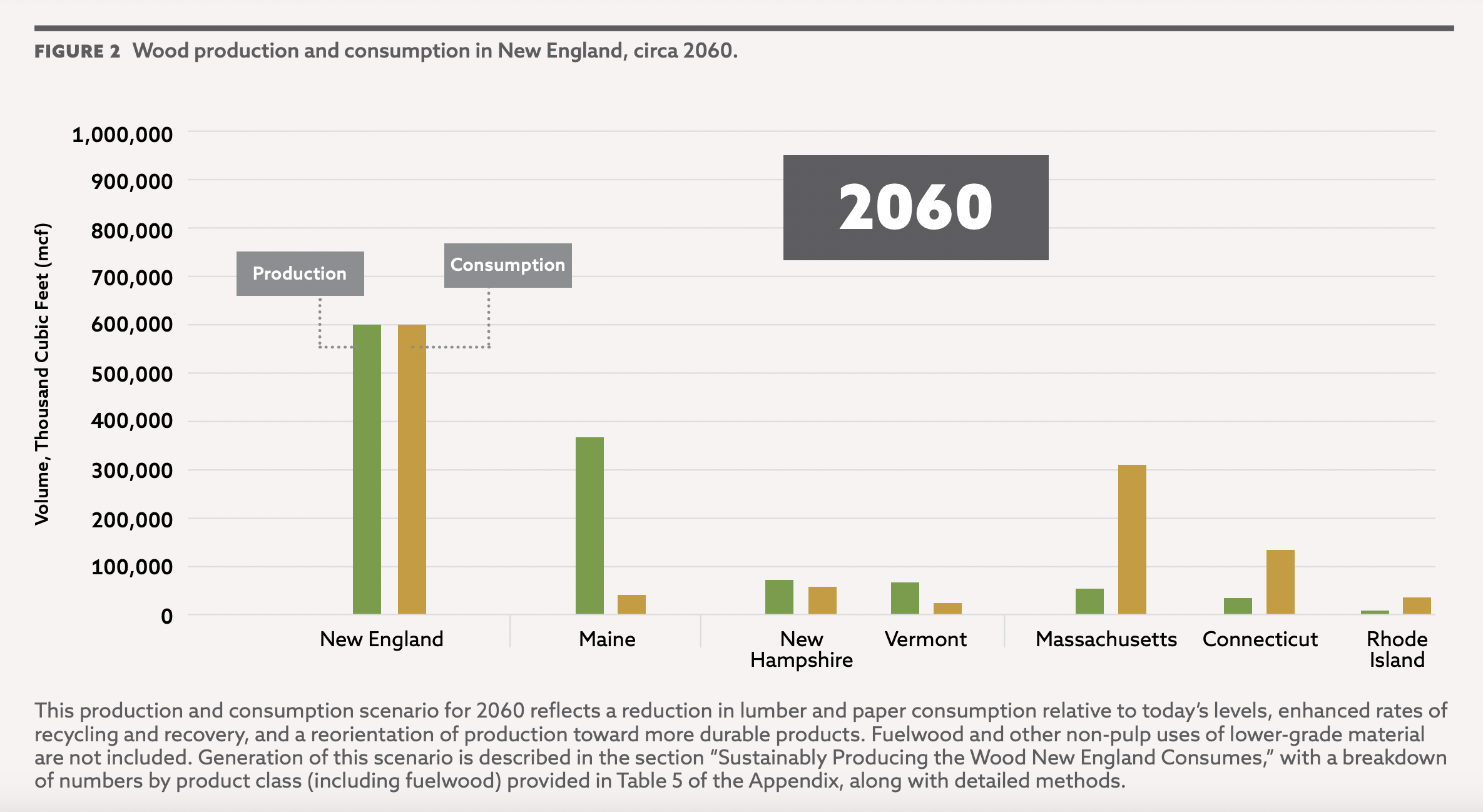

In this publication, we seek to address that Illusion, first by quantifying the gap between production and consumption in New England’s states. We found that, as a region, New England produces about three-quarters of the wood it consumes: 59 percent of its lumber and 80 percent of the raw material for paper (Figure 1). More stark are the disparities within the region: The three southern New England states produce only seven percent of the volume of wood they consume, despite being 60 percent forested. Vermont and New Hampshire produce a bit more than what’s consumed: 104 percent and 147 percent, respectively. Finally, Maine produces 325 percent of the volume of lumber and pulpwood that it consumes. That means that 70 percent of New England’s production comes from Maine, while 70 percent of the region’s consumption occurs in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

“70 percent of the region’s consumption occurs in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.”

This is not surprising: Most of the region’s population resides in southern New England, which has less forest. But even if Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts can’t produce all the wood they consume, they do have the capacity to do far more in terms of both increasing production and reducing consumption, particularly in addressing their lumber deficit. As a region, New England has the same per capita proportion of forest as the nation as a whole: about two acres per person. Even if New England cannot produce every single stick of lumber and piece of paper it consumes (because different kinds of wood products flow in and out of the region), we certainly do have the capacity, and therefore the responsibility, to produce a total volume that is in balance with what we use.

Courtesy of MassWoods, from Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’

In Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’, we set forth an ambitious vision for 2060 that would not only remedy these imbalances (Figure 2), but also dramatically enhance protection of our forests and propel us toward meeting urgent climate and biodiversity goals. We propose three primary pathways to achieving this vision:

Protect New England’s forest

Greatly accelerate protection of forest through a combination of fee purchase or conservation easements, aiming at safeguarding 70 percent of the landscape by 2060.

Set aside at least 10 percent of New England in Wildlands.

Implement “no-net-loss” policies that strongly encourage clustered development and redevelopment to prevent loss of forest to low-density rural sprawl.

Reduce and reorient wood consumption while enhancing recycling

Reduce overall wood consumption by 25 percent, even while increasing the use of wood in one sector by committing to building affordable housing and replacing steel and concrete construction with wood wherever possible. This is important in solving other environmental problems.

Reduce paper consumption by 25 percent.

Improve paper recycling and wood reclamation by 50 percent.

Expand ecological forestry while reorienting toward durable products

Expand ecological forestry to include 20 million acres carefully managed for both ecological values and wood production. This would include, in one scenario, about 50 percent of family, nonprofit, and public forests, and all corporate forests; in all covering about half the region and producing 0.4 cords/acre/year (Table 1 ).

Reorient productive forest management away from pulp and toward timber through forestry aimed at durable, high-market-value products.

Invest strategically in forest industry infrastructure throughout the region to help reach the goal of producing most of the wood products New England uses, simultaneously expanding employment opportunities.

Courtesy of MassWoods, from Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’

Taken together, these steps illustrate the sheer scale of what would be required to move beyond the Illusion. To be clear, this is not simply a matter of ramping up production to erase the production-consumption imbalance. Rather, moving beyond the Illusion requires a holistic and deliberate approach that safeguards the ecological, economic, and social values of New England’s forest while sustainably meeting our resource needs. None of these steps will be easy. But by advancing them side by side, we have the opportunity to take regional responsibility and permanently safeguard the innumerable values our forests afford us in this era of uncertainty.

“moving beyond the Illusion requires a holistic and deliberate approach that safeguards the ecological, economic, and social values of New England’s forest while sustainably meeting our resource needs.”

Given the planetary emergency that we face, we do not believe the Illusion can be dispelled by merely tweaking tax policies and market incentives. Rather, a broad movement among family forest owners, similar in scale and spirit to the Victory Gardens of World War II, will be needed—and will need to be carried on for decades, often through successive owners. At the same time, an equally broad shift in the incentive structure for large tracts of forest currently in the hands of corporate owners will also be needed. All told, we believe this transformation will require not only a cultural shift in how we think about our forests but also a massive public investment scaled to the environmental and societal challenges we face, and designed to support an enduring ecological approach to stewardship.

Our intention with this vision is to be illustrative, not prescriptive. There are other ways the harvested forest acreage might be distributed, for example. Beyond that, there may be other ways in which we could collectively and creatively envision a sustainable, vibrant future for our forest and communities, with the benefits we derive from the land widely and equitably shared. Determining how, precisely, we achieve such a future is the next challenge we must face. Our forest has long blessed us with its resilience and countless other gifts; it is time we reciprocated by caring for it with real rather than illusory values.

Woodland: A Well-Managed Forest. Photo © Tony D’Amato

Wildland: Pisgah Forest, New Hampshire. Photo © David Foster

ReflectionsToward a Culture of Forestry Sustaining Forests

Michael Snyder, Licensed Forester and author of Woods Whys—An Exploration of Forests and Forestry, Greenfire Enterprises, Vermont.

The new publication, Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’, provides a large part of what has been missing from the current dialogue about forests and forestry. Notably, it focuses on our shared interests and responsibility. Not for nothing, it places primacy on that responsibility, especially our responsibility to realistically consider where our wood products come from and how much we use them in our daily lives. This is key to the conversation, and there’s no getting around it.

The authors present a coherent, integrated view—not just one thing; there’s something in it for everyone to like and maybe to be a little uncomfortable about—with a data-driven reflection on past and current conditions and with bold, actionable proposed steps forward.

Focusing more specifically on implementation of those action steps on public forestlands, I come with a perspective and belief that public lands are special for many reasons. I suspect this is true for most of us. Of course, the mix and order of reasons will vary among us.

For me, public lands are special because they are distinct from private forests, yet they serve in so many ways as powerful complements to family forest ownerships. Indeed, public lands often function as ecological anchors and connectors, as forest management access facilitators, and as social and recreational hubs, all embedded within a larger landscape of private family forest ownerships.

“public lands often function as ecological anchors and connectors, as forest management access facilitators, and as social and recreational hubs, all embedded within a larger landscape of private family forest ownerships.”

Moreover, they are places where we have an opportunity, and I believe a responsibility, to try things many family forest owners would not likely attempt. To pilot, to monitor, to experiment, to test a range of new stewardship strategies—over long planning and management horizons—and to demonstrate and share lessons learned, best practices, and novel management approaches. This has always been very powerful and can be even more so.

Public forests also tend to have strong and clear statutory mandates—mandates that are consistent with the goals and strategies outlined in Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’. This is certainly true in Vermont, where the enabling statutes make very clear the productive and protective purposes of public lands and the role of multi-purpose forest management in effecting the achievement of those goals.

In these ways, existing and future public forests are very well positioned to help implement the strategies outlined in Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’—especially Step One (Expanding Forest Protection) and Step Three (Expanding Ecological Forestry). Public forests have always played a significant role in protecting forests from permanent conversion through fee-simple ownership. It’s reasonable to imagine this continuing.

In Vermont we have as a guide Vermont Conservation Design (VCD), a framework for maintaining an ecologically functional and connected landscape, including targets for reserves of lands of various representative types and conditions, embedded and connected within a larger landscape of working forests and farms and communities. And as of 2023 we have Act 59, the community resilience and biodiversity protection law that requires permanent protection of 30 percent of the Vermont landscape by 2030 and 50 percent by 2050. It relies heavily on VCD, and it specifically requires state-owned forestlands to contribute toward those goals.

It would seem straightforward to build on what already exists. However, the challenges will include not only finding adequate funding for protecting land, but also increasing capacity for the professionals and systems that do this work, both within public agencies and among partner organizations.

Camel’s Hump State Forest, Vermont, a Mix of Wildland and Woodland. Photo © Caitlin Littlefield

And that brings us to Step Three: Expanding Ecological Forestry.

Public lands are also well positioned to contribute here. The authors are right to highlight the significant expertise and robust planning and oversight that goes into public lands management. Who better, then, to lead the way in sustainable wood production through “Expanded Ecological Forestry?” Especially when, as the authors note, the current volume of harvest on public lands is “minimal,” providing ample opportunity for thoughtful expansion.

Instead, the Vermont version of recent anti-logging-on-public-lands activism has pointed to this low level of harvests as a reason for doing away with harvesting altogether. It’s so small, it won’t matter if it goes to zero, seems to be the thinking.

This reveals a massive blind spot—not seeing that even a modest state lands project can make or break a small, rural logging enterprise in any given year, with a cascade of ill effects in that community. On the contrary, this low level of harvest on public lands should be an embarrassment to us all. Not just foresters. I mean all of us—considering our shared interest and responsibility that is at the core of this work.

Given the expertise of state lands managers, that robust and public planning process, and the opportunities for application of ecological silviculture, this is one place where more of our wood should come from if we are to succeed in meeting the challenge before us.

I thank the authors for calling for a modernized forest economy—preferably with a re-energized culture of forestry along with it. We need a revised, coherent system of education, training, regulation, incentives, and investments all along the forest economy value chain. This would include innovative support for forestland owners, foresters, loggers, truckers, primary processing and secondary manufacturing facilities, and artisanal woodcrafting, as well as emerging twenty-first-century forest products and applications like wood-based insulation and mass timber construction.

We have the modern expertise and we have the technology. But none of that will matter without a culture—a mindset—of ecological forestry that proudly includes both passive and active management on all lands, public and private. We need less heat and more light. Light that brings bright, drama-free clarity to our consumption of wood, our broad dependence on forests, and the spectacular potential for ecological forestry to hold it all together in the real world.

The historic, massive cultural shift the authors rightly say is needed to pull off the bold vision of Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’ is perhaps the most significant challenge of all. The desired future condition, as imagined here and in Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities, will not happen without a marketplace, workforce, and infrastructure of forestry for forests and people—a viable forest economy, that is—and a revival of the rural culture that sustains it.

Reflections Forest Time

Lincoln Fish, Consulting Forester, Bay State Forestry Service, Athol, Massachusetts

It’s been nearly 44 years since I took on the job of consulting forester. Many of the clients I work for now are the grandchildren of the original owners. The leading lights of the conservation commissions and land trusts whose land I manage have changed many times. Each new owner of the same forest will have their own values and conception of what forestry is. The forest owner-forester connection needs to be renewed with each change, and it doesn’t always go smoothly.

Jess Fish’s encouragement for a growing oak. Photo © Lincoln Fish

In those four-plus decades, I have had to sift through the layers of what we do in the woods, separating the wheat of what is important and lasting from the chaff of what is minor and ephemeral. Time and time again, the visceral reaction of observers (from friends and clients to coffee shop gossips) about the slash and stumps on a logging job has long faded away before the grandeur of thrifty trees responding to the nourishing light afforded them by a thinning arrives. That forest time and human time operate on different schedules should not be news, yet I am still surprised when I visit a woodlot I thinned years ago and find that during the many human dramas that have come and gone since that thinning, trees really do grow!

From my vantage as a consultant, the opportunity to practice ecological forestry has never been better. In many respects, this evolution in the way forestry can be practiced is the most exciting development that I have seen during my forestry career. Beginning with the Forest Stewardship Program, moving into Foresters for the Birds and now Climate Forestry (all programs administered by Massachusetts Division of Conservation and Recreation, DCR) the focus of management planning has changed so that wildlife habitat and non-commercial forest features are placed on equal footing with the growing of timber. Recommended practices to enhance diverse forest values can now be funded through DCR, NRCS (Natural Resource Conservation Service, a federal agency with an office in each county), and private agencies such as the Family Forest Carbon Program. These practices can include things like planting trees; protecting those trees from deer browse; manipulating a young second-growth forest to mimic the conditions found in an old-growth forest (without waiting 200 years for those conditions to develop); and my personal favorite, invasive plant control.

Ecological forestry involves spending more time growing trees than you spend harvesting them. It is the forester’s opportunity to give back. In general, this approach involves applying human effort to making conditions in the forest more conducive to vigorous growth (including trees unsuitable for timber that have wildlife or other ecological value), then standing back to let time and nature build on that effort. That initial effort is the building block of ecological forestry. Because our human consciousness cannot move slowly enough to watch its impact over several decades, it is easy to lose track of the values being tended. This leads me to my greatest concern about ecological forestry. While practices may be easier to implement now, societal pressures may be making it more difficult to maintain those practices long enough for them to bear fruit.

“Ecological forestry involves spending more time growing trees than you spend harvesting them. It is the forester’s opportunity to give back.”

Let me illustrate with some recent stories.

First, Story A, is a 150-acre property I have worked on since the early 1980s. Protected from development by a conservation restriction, it was thinned several times over the years. The thrifty trees grew large in response, and by 2020, there were numerous groves of white pine and oak 2’ diameter and greater. The next steps planned were to start creating gaps to harvest some of the timber, allow the best trees to continue to grow, and establish diverse regeneration. Grants were available for invasive plant control and deer browse protection so that the seedlings would thrive. Short ending to the story: The landowner got dementia and the son took over management. A logging contractor working next door convinced the son that it would be “simpler” to have them do the harvest and supply their own forester to lay out the job. The prescription of that forester could be summed up in the phrase “find the big ones,” which they did: cutting the best trees and leaving the rest, with no thought to regeneration. So much for ecological forestry on that lot.

Story B started in a similar way, but it took an opposite turn. It is about a 120-acre lot that I managed for 30 years following another forester for 15 years before that, going back to the late 1970s. Again, the forest was worked by a series of thinnings plus invasive plant control. Most of the property is now occupied by large timber, notably a stand of 2’–3’ diameter red oak. The owners got old, and being conservation minded, they offered the property to a land trust. The land trust folks “discovered” the large oaks and decided it would be perfect for a hands-off old growth forest. They informally told me: “good job, those trees are half-way to old growth, but your services won’t be needed anymore.”

So much for ecological forestry on that property, too. There was no acknowledgement that forestry is the reason those trees are as large as they are, and that those old-growth characteristics they covet are much closer to existence due to the 45 years of thinning. To be clear, I am happy the land is protected from development. The lost opportunity is the potential to produce some of the building materials that society needs along with the creation of more old growth characteristics (canopy gaps, diversified age classes, large trees) on this very appropriate property that had been groomed for that purpose for half a century.

These stories went in different directions, but they both point out that the time frame of ecological forestry is so long that it is vulnerable to being short circuited. And in fact, they work together: The impact of many Story B’s will over time exacerbate the forces that create Story A. The impact of Story B could be alleviated if along with the love of old growth we could also love places where our most beautiful and sustainable building material can be grown and utilized. In the current belief system of one part of the land protection community, however, the only valuable land is land on which manipulation by humans is forbidden.

“the time frame of ecological forestry is so long that it is vulnerable to being short circuited”

Embracing her college tuition. Photo © Jennifer Fish

I am not blameless in these two stories. I might have changed the outcome of either had I spent more time with the landowners and their families, romancing them with the story of ecological forestry. Like most consultants I usually have more work than I can do and will often cut short landowner interactions in order to get on to other jobs. I like the idea of the new DCR program to fund forester time with landowners. It’s a new era; we have the funding to accomplish ecological forestry. We have to be more effective in conveying our passion about it to our landowners and to the public, so that more of them will be inclined not just to get started, but to stay the course.

This brings me to Story C. I have a neighbor who received a forest stand improvement grant. This week we both grabbed our saws and went to work implementing that grant. It’s my version of treasure hunting, finding and releasing such gems as a thrifty oak sapling, a beech relatively free of disease, a cavity-riddled red maple covered by grape vines that can be stimulated by light to produce fruit, a yellow birch valued for bird habitat and for potential lumber, a patch of second-year pine seedlings. We stopped to compare notes after each tank of gas, weighing the utility of our decisions and actions to wildlife, forest health, the climate, and to humanity. He is not overly motivated by the monetary value of eventual forest products, yet he appreciates their value to society. He is motivated by the emotional reward of making things better. At the end of our day, he said “This seems like something you would want to do in your woods every 10 years.” For ecological forestry to prevail, we need to make sure the next owner also thinks the same way.

A break from firewood cutting. Photo © Jennifer Fish

Oak saplings filling a harvest gap. Photo © Lincoln Fish

ReflectionsBeyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’: Connecting People with Forests and Forest Products

Julie Renaud Evans, Program Director, Northern Forest Center

I grew up in central Massachusetts at the foot of Mount Wachusett and have spent my adult life in northern New Hampshire. The people, landscapes, ecology, and economies are simultaneously similar and very different. This is why I appreciate the Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’ report so much: It highlights how a disconnected populace can come together to address the regional imbalance of wood production and wood consumption for the good of the region and the globe.

This is a very important and timely report as we experience global climate change, increasing urban and suburban populations, and declining rural communities. I appreciate the regional landscape view and the truth-telling; it is an honest look at how we live and provide for our lifestyles, how we use our resources—the regional and global impacts that ensue, and the current imbalance in New England of wood use, including how our consumptive habits are out of line with nature.

At the Northern Forest Center, we think about and advocate for forests from a holistic perspective. Our society depends on economic, ecological, and social benefits from this forested landscape that we must balance and maintain now and into the future. This report offers a pathway to a sustainable New England region, where the wood we grow equals or exceeds the wood we consume, and the forest can provide both forest products and carbon storage. Further, this report makes the case for better balancing wood production with wood consumption across our north-south geography.

Northern forests have always provided New England residents with lumber to build homes, every kind of paper, and vast opportunities for recreation in all forms. Shifting some of this production to southern New England forests will reduce the pressure for harvest on northern forests, which will allow some landowners to evolve away from an industrial extraction mindset of short financial gains. Such narrow objectives have unfortunately resulted in areas of over-harvesting and degraded ecological health. Southern New England landowners, including both family forest owners and state agencies managing public lands, can pick up the slack by harvesting more wood and actively participating in a regional wood basket. Achieving this goal will require commitment, work, choices, and habit shifts from consumers, landowners, land managers, entrepreneurs, and policymakers.

We all need to reduce consumption, including products made from wood. At the same time, renewable wood products are key in the fight against climate change, and markets for these products are an essential part of the economics that enable good forestry. This is an opportunity to re-orient and re-tool our industries for products and markets that will sustain forest products industries and jobs and highlight the role that forest products—not just forest management—can play in addressing climate change by reducing carbon emissions. Products like mass timber, wood insulation, wood-based materials as replacements for single-use plastics, and efficient forms of bioenergy are all real examples of how the wood products we produce are also contributing to a net reduction in carbon production. Ultimately, the ideal is to manage our forests—in both southern and northern New England—with ecologically-based management strategies to keep them healthy, productive, and contributing to climate mitigation, and to balance harvesting so that no area is subject to unsustainable harvesting.

“Ultimately, the ideal is to manage our forests—in both southern and northern New England—with ecologically-based management strategies to keep them healthy, productive, and contributing to climate mitigation, and to balance harvesting so that no area is subject to unsustainable harvesting.”

Logs on the Landing, Winter. Photo © Ross Caron

A Timber Frame Building at Merck Forest and Farmland Center, Vermont. Photo Courtesy of Merck Forest and Farmland Center

We would like to see the forest industry, state governments, NGO partners, and consumers work both independently and collaboratively to aggressively pursue these product and market expansions with capital and capacity investments. We also see this as an opportunity to attract a new generation of entrepreneurs and workers—both in the woods and in wood-based manufacturing—who are excited that ecological forestry and wood products can contribute significant climate solutions as much as heat pumps and electric cars can. This requires consistent public and private investments in workforce development and training programs. A coordinated, robust regional effort in these investments would result in healthier landscapes, lifestyles, and local land-based economies.

The report rightfully stresses the need to increase harvesting on both family forests and public lands to meet wood demand. We find some of the best ecological forestry in New England practiced on public land. There are entire teams planning, considering impacts, gathering public input, and implementing any treatment. I am confident these well-managed forests can produce products that will help us mitigate climate change while also maintaining critical ecological functions and storing carbon. Arguments that advance the notion that the best response to climate change is to leave forests alone and cut nothing are deeply flawed. These anti-harvesting campaigns often target public lands for this “carbon-storage-only” strategy—but this would only drive more harvesting to private lands, or to other parts of the world. It is senseless that southern New England is 60 percent forested but produces only seven percent of the wood it consumes. If leaders and legislators are swayed by oversimplified “no cutting” campaigns, they will take action that exacerbates the imbalance and yet does nothing to reduce climate impact.

One kind of public forest offers a special opportunity to reach the regional vision laid out in Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’. We can use town and community forests to practice and demonstrate ecological forestry, with tree harvesting that benefits the climate through silviculture and best management practices. We can use wood from town and community forests in our schools, libraries, and town buildings, so that they showcase new, innovative uses of wood fiber. Town and community forests are the ultimate opportunity to manage for many uses, for many benefits, with highest priority on climate, education, and community stewardship. New England has many fine examples of community forests, but could use far more—why not one in every town?

In their own words, the authors’ ambitious vision requires a “holistic and deliberate approach that safeguards the ecological, economic, and social values of New England’s forests while sustainably meeting our resource needs.” I encourage you to spread this report widely, to share it with policymakers and leaders, to embrace and to speak up for the proposed solutions. With shared conviction we can indeed realize the vision laid out for us.

The Northern Forest Center is a regional innovation and investment partner creating rural vibrancy by connecting people, economy, and the forested landscape across the 30-million-acre Northern Forest of northern Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. The Center works across economic, community, and conservation disciplines to position the Northern Forest for economic prosperity and ecological resilience.

ReflectionsWildlands Should Not Compete with Ecological Forestry

David Publicover, Senior Staff Scientist (retired), Appalachian Mountain Club

A Forest Field Tour Hosted by Appalachian Mountain Club and the Author. Photo © Sarah Nelson

Much of the discussion over “local sustainability” has focused on agriculture and food supply. Yet New England is overwhelmingly forested. By bringing forests and wood supply into the discussion, Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’ (and its predecessor) makes an important contribution to this discussion. There is a lot in here that I agree with, and a bit that I do not.

First, I am struck by how familiar these debates are. The balance between Wildlands and Woodlands as competing (but complementary) land uses hearkens back to the wilderness versus wise use arguments of John Muir and Gifford Pinchot. On actively managed lands, the tension between “production” and “ecological” models of forest management trace back at least as far as Aldo Leopold’s Group A and Group B foresters set forth in 1949’s A Sand County Almanac. The issues being debated may have changed from wildlife and wilderness recreation to biodiversity and carbon storage, but the basic question remains: How do we best use our natural landscape to provide benefits to society while maintaining its ecological integrity?

The authors categorize the forest landscape by ownership. I think of it in different boxes:

Natural areas: All areas specifically managed to maintain a natural condition with minimal human interference, including both Wildlands as strictly defined in the recent Wildlands in New England report and additional areas designated in management plans even if not permanently protected as such. These are predominantly on public and NGO lands.

Production forests: Lands whose primary focus is the economically efficient production of timber, primarily on large commercial ownerships in northern New England.

Ecologically-managed forests: Lands actively managed for timber but with a primary focus on the maintenance of relatively natural (and mostly older) forests. These are mostly public and NGO lands, as well as some family forests. (In practice, the distinction between ecological and production forestry is not a clear line but more of a gradient.)

Unmanaged forests: This includes land that is left alone, as well as land where timber is occasionally harvested, but which does not have long-term goals or a management plan to achieve them. This includes most family forests and other smaller private ownerships. (Those portions of public and NGO ownerships where timber is not harvested are usually designated in management plans as some type of natural area, even if other values such as recreation are the primary focus. They would be considered “passively managed” rather than unmanaged.)

The vision set forth in the paper proposes an increase in the acreage devoted to both Wildlands and ecological forestry, a vision I wholeheartedly agree with. The more of our landscape that can be managed with a specific focus on maintaining ecological integrity, the better off we will be.

“The more of our landscape that can be managed with a specific focus on maintaining ecological integrity, the better off we will be.”

In promoting these transitions, we should recognize that there is more to be gained by transferring land into the desirable pools (Wildlands/natural areas and ecological forestry) than by transferring land between them. In northern New England, these transitions should primarily come from production forestry lands, accomplished either through a change in ownership (i.e., acquisition by public agencies, tribes, or NGOs) or a change in financial drivers that would incentivize older, higher volume forests (such as carbon pricing). In southern New England, they should primarily come from the unmanaged forest pool.

Eliminating or greatly reducing timber management on public lands (the goal of proforestation) would eliminate harvesting from the ecological forestry pool, which is counterproductive—we want more, not less, of this type of management. However, while ecological forestry on public lands provides many benefits, a significant increase in the amount of public land devoted to timber management would also be counterproductive, as it would subtract from some form of natural area management—the most limited component of the landscape. Management as natural areas (and ideally designation as some form of Wildland) should be the dominant use of most public lands (particularly large federal and state lands), though it need not be the exclusive use.

Old Growth Black Gum Forest, New Gloucester, Maine. Photo © Liz Thompson

The public and philanthropic funding available for these transitions (for both land acquisition and management incentives), as well as the political effort needed to enact them, will always fall far short of the need. It is important that these be used in the most effective manner possible, particularly in the near term. Ideally, conservation efforts should ensure both permanent protection and improved management (recognizing that not all programs are designed to do both). Land conservation that provides permanent protection, but that does not actually change on-the-ground practices, may have significant long-term benefit but little near-term benefit unless the land was at significant risk of conversion.

Specifically, I have concluded that large working forest easements on corporate lands are not the wisest use of available funds (as a recent paper from Harvard Forest has also argued). While these easements may prove to be valuable long-term investments, in the urgent near term they accomplish very little. These lands are not significantly threatened by development. Corporate lands with an easement remain in the production forestry pool, with little to no increase in either the Wildlands or ecological forestry pools. Easements should focus on lands at high risk of conversion; funds available for the conservation of corporate lands would be better spent on full-fee acquisition of a smaller acreage, with a resulting significant change in management.

Commercial thinning of a mature spruce-fir stand. Photo © Steve Tatko

The paper makes another important contribution by emphasizing the need to reduce our consumption of wood fiber as a critical step toward treating our forests more gently. Too often we treat the societal demand for wood as an unchangeable given. A recent example of this comes from Maine, which has done a lot of good work examining how the state’s forests can contribute to an overall strategy of climate change adaptation and mitigation. Yet these policies and analyses (such as the recent Forest Carbon for Commercial Landowners study) have been unduly constrained by a requirement that overall harvest levels do not decline. Eliminating this requirement opens up additional possibilities for a sustainable future.

Finally, I have heard a legitimate concern about the title. The phrase “Illusion of Preservation” can easily be heard as an argument against wilderness, and may be used by those opposed to additional Wildlands in the same way William Cronon’s “The Trouble with Wilderness” was used earlier. A close reading of the paper makes clear that this is not the intent—it provides a strong argument for increasing both wild areas and ecologically sound forestry. We must be alert and ready to counter those who would pit one against the other.

ResolutionThe Resolution of Preservation and Management

Brian Donahue, David Foster, and Caitlin Littlefield

We are among the authors of Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’. This paper (summarized earlier in this issue of From the Ground Up) asks whether New England can sustainably produce the wood we need, while protecting all the other social and ecological benefits of a diverse forest. The answer is: Yes, we can. But will we?

“The Illusion of Preservation” is a provocative phrase. That title comes from a study published by Harvard Forest over 20 years ago, which found that the state of Massachusetts harvests only about two percent of the wood it consumes. Not much has changed since then—this time, we credited Massachusetts with seven percent. Any improvement was in the method of calculation, not in the actual harvest levels.

But where is the “illusion?” Preserving more land in a passively managed natural state is not illusory; it is necessary and good. Indeed, the authors have long been proponents of greatly increasing the acreage of protected Wildlands in New England to at least 10 percent of the region, as discussed in a recent report by Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands, & Communities.

The illusion of preservation arises when we focus instinctively on just leaving the forest alone, and reject the harvesting of local forests, ignoring where our wood comes from. The illusion lies in insisting that unharvested forest is always the best forest here, in our own backyard—leaving the problem of obtaining what we use to somebody else, where we don’t have to watch. Resolving that paradox requires harvesting local forests in better ways, and also in consuming less wood.

But intertwined with the illusion of preservation is a second, seemingly opposing modern affliction: We might call it “the compulsion of management.” Again, some management is necessary and good: people need houses, and wood is a wonderful material. People have been stewarding the forest in sustainable ways for thousands of years. As an industrial society that inevitably requires a large volume of wood products and therefore manages forests with an intensity that exceeds that of indigenous stewardship by orders of magnitude, we are particularly challenged to do so responsibly. But the need for considerable management does not mean that everything must be actively managed. The compulsion of management occurs when we become overly inclined to manage all forests for human benefit, or just for their own good, and allow little or no place for passively managed wildlands.

Clashes between preservation and utilitarian management have dogged forest conservation for over a century, since the days of Gifford Pinchot and John Muir. The cardinal sin of preaching preservation alone is hypocrisy—ignoring our need for wood and where it comes from. The corresponding sin of preaching only management is hubris—the belief that we can manage forests better than nature can.

Few people who actually spend time in the woods—ecologists, foresters, loggers, conservationists of every stripe (including Pinchot and Muir themselves)—are guilty of either of these sins in such a simplistic way. Most support, in principle, the resolution of preservation and management: some kind of balance between passively managed reserves and actively managed forests, between Wildlands and Woodlands.

But how do we achieve a balance between ecological values and sustainable production in the face of a global market economy that rewards only the most economically “efficient” forms of extraction? This dilemma has opened a seemingly unbridgeable chasm between “intact nature” and “wood production” in many people’s minds, and on the landscape—perpetuating the conflict in practice.

Many preservationists, doubting that the extractive drive of the forest industry can be sufficiently restrained, push to maximize the amount of land managed passively solely to protect ecological values—hence, proposals to devote “Half Earth” to wild nature, and to dedicate all public forests to that cause. At the same time, sincere proponents of sustainable forestry struggle for incremental improvements in industrial logging, through easements, certifications, and incentives. In practice, neither resolves the issue. One flees from the market economy, the other caves to it. Together, they have led to a world where a meager scattering of wild reserves (currently little more than three percent of New England, for example) cannot adequately “balance” the impact of globally-expanding, intensively-managed, ecologically-simplified production forests and plantations.

In Beyond the ‘Illusion of Preservation’ we offer what we hope is a better resolution between preservation and management: one in which wood consumption is meaningfully curbed, passively managed Wildlands are greatly expanded, and the practice of ecological forestry moves from an extremely small percentage of the landscape to being practiced over some 20 million acres, or half of New England. By “ecological forestry” we mean a range of practices that put ecological values first, but maintain production by carefully thinning younger forests and eventually harvesting high-quality, mature timber.1

“By “ecological forestry” we mean a range of practices that put ecological values first, but maintain production by carefully thinning younger forests and eventually harvesting high-quality, mature timber.”

This would turn timber harvesting in New England on its head. It would require several decades of lighter cutting in the industrial forests of the north, moving them away from short-rotation intensive cutting while investing in their future. At the same time, it would mean more active management of the family-owned and public forests of central and southern New England, again aimed at long rotations. On the whole it would gradually lead to producing more lumber and less pulp; but just as important, it would enhance the carbon storage, biodiversity, and other ecological values of a diverse and complex forested landscape.

An Oak Shelterwood Treatment in Southern New England. Photo © Jeff Ward

Regeneration in a Recently Treated Spruce Stand. Photo © Tony D’Amato

Practicing such ecological forestry would necessarily increase the cost of wood products, but would also provide enormous benefits for society as a whole. This raises a key question: who would pay for that increased cost?

We can imagine three ways that the benefits of ecological forestry might be obtained, and they are not mutually exclusive. The first would be more expensive wood products for consumers. The second would be payments for carbon and other ecological services by governments. The third would be a lower rate of return for landowners.

First, some consumers might choose to pay more for wood products harvested through ecological approaches, much as some do for locally grown organic food. These consumers could include individual homeowners, builders, institutions, corporations, and government agencies. Governments can also encourage certain programs they support, such as affordable housing, to purchase ecologically harvested wood. For this to work, we would need more reliable ways for consumers to identify and reward ecological forest products, which is not an easy matter.

Governments can also directly reward landowners who follow sustainable practices and provide environmental benefits by paying them to cut more lightly, or to not cut at all. This has great promise, and we are seeing movement in that direction in the form of payments to compensate owners for allowing more carbon (in the form of trees) to accumulate on their land. But in our view such payments should encompass a much broader range of ecological benefits than simply standing carbon, which has the twin defects of oversimplifying the issue while employing a complicated metric which is difficult to accurately measure.

Such incentives also raise questions of equity and accountability. Who receives these payments, and why are they entitled to them? It makes little sense to us for those who have cut too heavily in the past to now be rewarded for a few years of cutting less, only to be free to return to cutting as they please when the carbon contract is over. It would make more sense for payments for ecological services to flow to those who are willing to make a real commitment to devote their property either to Wildlands, or to ecological forestry practices that will continue to yield climate and biodiversity benefits in perpetuity.

We believe such landowners exist, and that they are naturally inclined to absorb at least part of the cost of producing wood by ecological methods, and to wait longer for a slower return. They include family forest owners who want to pass their woodland on to their children in as good shape as they found it, or a little better. They include non-profit organizations whose mission includes land stewardship. They include community forests that exist to benefit local residents both economically and environmentally. They include tribes who were already caring for the land sustainably, time out of mind, before it was expropriated. They include public forests that are carefully managed.

If we as a society decide to pay for the ecological benefits of treating the land with grace, why not direct those funds to people who are inclined to do so anyway? Such owners will do it for a lower cost and can be trusted to do it forever, if properly supported. They are a better long-term investment than those who will only do it if we pay them more than what they could earn by rapidly extracting commodities, and who will return to that as soon as the payments cease.

The resolution of preservation and management requires us to move beyond the biggest illusion of all: that the market knows what is best for us. If we want to see the spread of ecological forestry across twenty million New England acres to help mitigate and adapt to climate change, provide for biodiversity, and meet our legitimate need for wood, the best use for public and philanthropic funds may be to move forestland steadily into the hands of landowners who are committed to those aims.

1 Ecological approaches to forestry vary, and will be explored in a future issue of From the Ground Up. A few good starting points might include work by Mitch Lansky and the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners on Low Impact Forestry, New England Forestry Foundation’s Exemplary Forestry, the Forest Ecosystem Conservation approach of Vermont Family Forests, Ecological Silviculture: Foundations and Applications by Brian Palik and others (reviewed by the Forest Stewards Guild), and the Origins of Ecological Forestry in North America by Tony D’Amato and others.

Caitlin Littlefield is a landscape ecologist who works at the intersection of forest ecology, conservation biology, and climate adaptation science. She links field data, climate data, and landscape models to understand how forests and the species therein are responding to global change, and she works closely with land managers to identify and prioritize adaptation strategies such as enhancing landscape connectivity and promoting recovery from disturbance. Underpinning all of Caitlin’s work is her deep commitment to inclusive and equitable conservation and climate adaptation solution-building. She holds a PhD in landscape ecology from the University of Washington, an MS in forest ecology from the University of Vermont, and a BA in conservation biology from Middlebury College.

Brian Donahue is Professor Emeritus of American Environmental Studies at Brandeis University, and a farm and forest policy consultant. He co-founded and for 12 years directed Land’s Sake, a non-profit community farm in Weston, Massachusetts, and now co-owns and manages a farm in western Massachusetts. He sits on the boards of The Massachusetts Woodland Institute, The Friends of Spannocchia, and The Land Institute. Brian is author of Reclaiming the Commons: Community Farms and Forests in a New England Town (1999) and The Great Meadow: Farmers and the Land in Colonial Concord (2004). He is co-author of Wildlands and Woodlands, Farmlands and Communities (2017) and A New England Food Vision (2014).

David Foster is an ecologist, Director Emeritus of the Harvard Forest, and President Emeritus of the Highstead Foundation. He co-founded the Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities initiative in 2010 and was lead writer of Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future in 2023. David has written and edited books including Thoreau’s Country: Journey Through a Transformed Landscape; Forests in Time: The Environmental Consequences of 1,000 Years of Change in New England; Hemlock: A Forest Giant on the Edge; and A Meeting of Land and Sea: The Nature and Future of Martha’s Vineyard.

Responses from Our Readers

Beyond the Beyond: A Reader Response by Robert T. Perschel

READ MORE →The Many Illusions of the ‘Illusion of Preservation:’ A Reader Response by Zack Porter

READ MORE →Landscape Scale Wildlands in Northern New England Threatened by Friendly Fire: A Reader Response by Jamie Sayen

READ MORE →