Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future: A Review

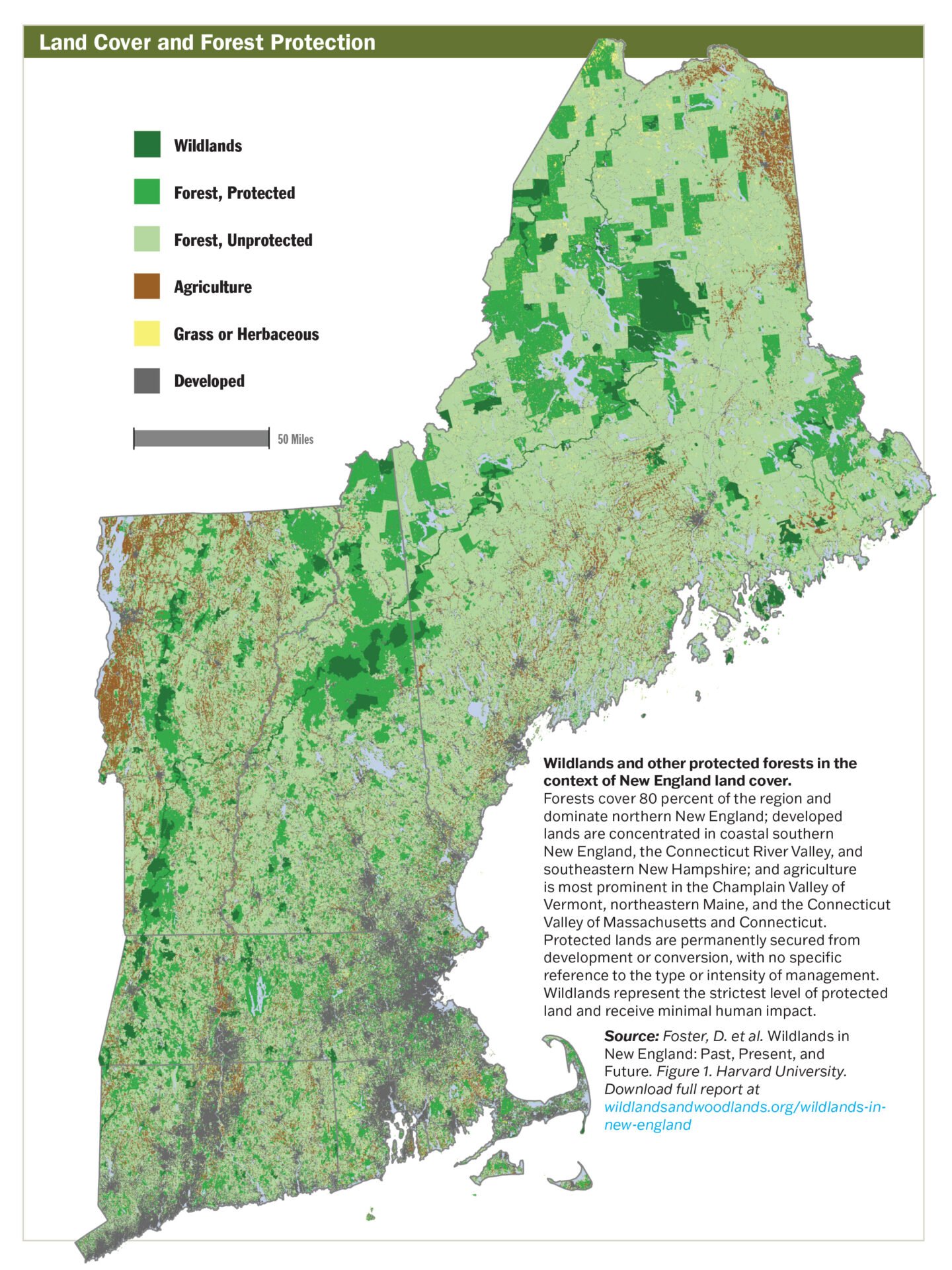

Wildlands and other protected forests in the context of New England land cover. Forests cover 80 percent of the region and dominate northern New England; developed lands are concentrated in coastal southern New England, the Connecticut River Valley, and southeastern New Hampshire; and agriculture is most prominent in the Champlain Valley of Vermont, northeastern Maine, and the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts and Connecticut. Protected lands are permanently secured from development or conversion, with no specific reference to the type or intensity of management. Wildlands represent the strictest level of protected land and receive minimal human impact.

New England is the most forested region in the United States, with 81 percent forest cover. Wild forests offer low-cost opportunities to welcome old forests back, store immense amounts of carbon, support wildlife, and provide a host of other ecosystem services that are otherwise expensive or impossible to replace. This can all be done simultaneously by protecting Wildlands.

This spring, Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities released Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future (WiNE), the first study in the U.S. to inventory and develop an interactive map of all conserved lands in one region that intentionally allow natural processes to unfold without the intervention of active management.

WiNE marks a major advance in efforts to transform our region’s conservation conversation about seeking equitable ways to meet human needs while preserving biological diversity and reversing alarming trends associated with anthropogenic climate change. I hope the WiNE report inspires other regions to produce similar studies that can be combined into a continental-wide Wildlands inventory and map that boosts efforts to connect green spaces in densely populated communities with the largest and most remote Wildlands.

New England’s Forests

Forests are among Earth’s most diverse and valuable ecosystems. New England encompasses 40.2 million acres, with 32.6 million acres forested. Wildlands in New England identified 1.3 million acres of Wildlands.

WiNE describes how today’s young forests differ from presettlement forests: “Many features of thriving old-growth landscapes that were common four hundred years ago are rare, including immense old trees; large, downed trees that add complexity to the ground, streams, and lake shores; and deep, spongy soils occasionally churned into mounds and pits by immense windthrows.” It requires centuries of non-management to recover a broad array of old growth qualities. While many species—including black bear, moose, deer, beaver, bobcat, wild turkey, bald eagle, and osprey, have returned—wolves and cougars have not.

Wildlands sequester and store much more carbon than even the most carefully managed woodlands, and they provide a greater diversity of habitat associated with mature and older forests than managed lands. Wildlands in New England determined that 92 percent of New England’s Wildlands are highly climate resilient areas important to plant and animal movement across the region, as compared with 67 percent of “other protected lands” and 47 percent of “unprotected lands.” It also found that 82 percent of Wildlands have high biological diversity value, in contrast to only 38 percent of other protected lands and 18 percent of unprotected lands.

Wildlands in New England Report

The authors of Wildlands in New England (WiNE) developed a comprehensive, succinct definition of Wildlands:

‘Wildlands’ are tracts of any size and current condition, permanently protected from development, in which management is explicitly intended to allow natural processes to prevail with ‘free will’ and minimal human interference. Humans have been part of nature for millennia and can coexist within and with Wildlands without intentionally altering their structure, composition, or function.

The WiNE report established a set of criteria qualified Wildlands properties must meet: (1) Wildland Intent, (2) Management for an Untrammeled Condition, and (3) Permanent Protection (See pages 30-35 of the report).

The authors wrote:

The quality of wildness is defined not by the land’s history or its current condition but by its freedom to operate untrammeled today and in the future. Thus, a recent clear-cut, securely protected from human manipulation, will qualify as a Wildland if that intent is in place and is enduring. In contrast, an adjoining old-growth forest that is not fully secured from future manipulation or conversion is not yet a Wildland.

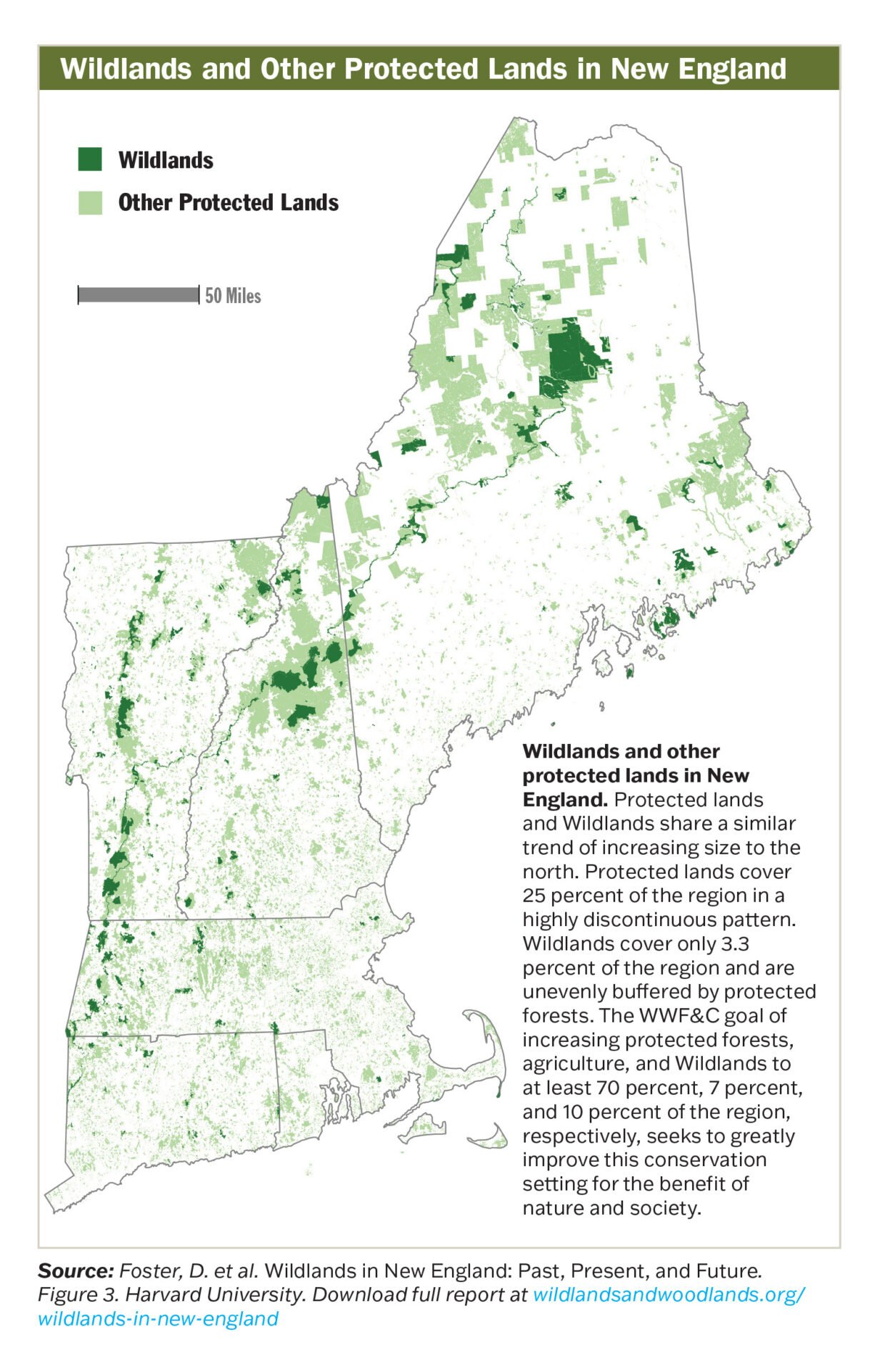

Wildlands and other protected lands in New England. Protected lands and Wildlands share a similar trend of increasing size to the north. Protected lands cover 25 percent of the region in a highly discontinuous pattern. Wildlands cover only 3.3 percent of the region and are unevenly buffered by protected forests. The WWF&C goal of increasing protected forests, agriculture, and Wildlands to at least 70 percent, 7 percent, and 10 percent of the region, respectively, seeks to greatly improve this conservation setting for the benefit of nature and society.

The study evaluated 652 properties suggested by more than 125 conservation professionals, and concluded that 426 properties encompassing 1,321,878 acres of lands met the three criteria for Wildlands. This represents 3.3 percent of New England’s land area, or 14.5 percent of the region’s 9.1 million acres of conservation lands. States own 39 percent of the Wildland acreage, while the federal government owns 36 percent. Land trusts own 24 percent in more than 140 properties, covering 312,641 acres. Educational institutions and private landowners possess the remaining one percent.

The Wildlands in New England Report identified 426 Wildland tracts scattered across the six states of New England. Here are examples from each state that illustrate some of the diversity in size, ownership, strength of protection, distribution, and ecological features.

Note: Strong protections include some “forever wild” deed restrictions or easement, and/or state or federal statutes. Weak Wildlands include management plans or organizational intent, without legal protections.

Maine

Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument (KWWNM)

Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument. Photo © Jym St. Pierre

Ownership: National Park Service

Size: 76,633 acres

Strength of Protection: Weak; currently lacks deed restriction or federal statute protection as Wildland. The National Park Service is developing a management plan. The public can learn about national monuments and support stronger Wildland status.

Ecological Features: The land is interspersed with a mosaic of forests, riparian habitat, rivers, and wetland areas that provide critical habitat for federally listed Canada lynx and Atlantic salmon. The patchwork of forests and wetlands and the predominantly native flora provides prime habitat for boreal and migratory forest birds. Many wet basins and riparian zones support important cultural materials that Penobscot people have sustainably harvested for generations. The forests, waterways, and wetlands continue to provide critical habitat and corridors for plants and wildlife, including threatened species such as Atlantic salmon, Canada lynx, and rare mussels and butterflies.

Brief Discussion: As an important travel corridor, the waters and immediately surrounding landscape are considered sacred by, and are vitally linked with, the cultural practices, ceremonial activities, and oral traditions of the Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot peoples. KWWNM was established in 2016 by President Barack Obama. It was donated to the National Park Service by Roxanne Quimby in an act of wildlands philanthropy. We encourage billionaires to emulate Quimby’s generosity and wisdom. Long may we celebrate her name.

Massachusetts

Muddy Pond Wilderness Preserve

Muddy Pond Wilderness Preserve. Photo © Harry White

Ownership: Northeast Wilderness Trust (NEWT)

Size: 277 acres

Strength of Protection: Weak; Muddy Pond Wilderness Preserve is currently protected by management plan, landowner intent (NEWT), and donor intent. NEWT is working to upgrade protection by conveying a forever-wild Conservation Restriction (easement) to a third party, however at the time of publication, this is not yet complete.

Ecological Features: Atlantic Coastal Pine Barrens, Coastal Plain Pond, globally rare species, two dozen vernal pools.

Brief Discussion: Muddy Pond Wilderness Preserve lies in the southeastern Massachusetts suburb of Kingston, about half an hour from each of Boston, New Bedford, and Cape Cod. It connects local students, residents, and visitors with wild nature and Wildland conservation.

New Hampshire

Pemigewasset Wilderness—White Mountain National Forest (WMNF)

Owls Head, White Mountain National Forest. Photo © Ken Gallagher

Ownership: White Mountain National Forest

Size: Approximately 45,000 acres

Strength of Protection: Very Strong; protected by 1984 New Hampshire Wilderness Act

Ecological Features: High elevation northern hardwoods.

Brief Discussion: The Pemigewasset Wilderness is the largest of six federal wilderness areas on the WMNF. Although intensely logged and burned from the 1880s into the 1940s, the area’s forests are recovering and rewilding remarkably across the topographically and ecologically diverse terrain that is accessible by a series of Wilderness trails.

Rhode Island

Oakland Forest

Oakland Forest. Photo courtesy of Aquidneck Land Trust

Ownership: Aquidneck Land Trust

Size: 20 acres

Strength of Protection: Weak, only a Wildland through a management plan.

Ecological Features: Ecologically unique old-growth American beech forest, with trees estimated to be between 200 and 300 years old. In addition to beech, the forest includes old-growth tree forms of other species including white oak and red maple.

Brief Discussion: The sole known Wildland in Rhode Island, Oakland Forest is dedicated as part of the Old Growth Forest Network. The property was once part of a “gentleman’s farm” owned by the Vanderbilt family in the 1800s and 1900s. There is a row of 100+ year old rhododendrons running through the forested part of the old estate.

Vermont

Peacham Bog Natural Area

Peacham Bog, Groton State Forest. Photo © Liz Thompson

Ownership: Groton State Park

Size: 544 acres

Strength of Protection: Strong; protected under state statute and management plan.

Ecological Features: Dwarf Shrub Bog, Black Spruce Woodland Bog, Black Spruce Swamp, Poor Fen, Red Spruce- Cinnamon Fern Swamp, Spruce- Fir-Tamarack Swamp and Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest.

Brief Discussion: Peacham Bog is one of Vermont’s largest and most intact peatlands. A boardwalk and interpretive sign offer easy access to visitors and researchers who can safely enjoy and study the bog without causing damage. The peatland, underlain by several feet of partially decomposed organic matter, has been the subject of ecological research and has provided a living classroom for countless students of ecology.

Connecticut

Connecticut College Natural Areas

Mamacoke Island, Connecticut College Natural Area. Photo courtesy of Connecticut College

Ownership: Connecticut College, one of only five colleges in New England that protects Wildlands. Connecticut College is a conservation model for other institutions in the region.

Size: Three parcels totaling about 200 acres.

Strength of Protection: Weak, relies on landowner intent.

Ecological Features: Coastal lowlands.

Brief Discussion: Established in 1952 through the leadership of Professor Richard Goodwin, the natural areas serve as outdoor classrooms, ecological research sites, and destinations of reflection for students, faculty, and visitors.

The WiNE Map identified major gaps and weaknesses in the existing Wildlands:

Degrees of protection ranged from strong legal documents, such as designated Wilderness and “forever wild” easements, to weaker protections such as agency policy without the force of law.

This chart indicates the state-by-state strength or weakness of wildlands of various ownerships. Strong protections include some “forever wild” type deed restriction/easement and/or state statute, and/or federal statute. Weak protections are those for which the Wildlands are secured solely through self-oversight as embodied in a management plan, organizational mission, executive decision, or expressed intent, etc. Chart by Brian Hall based on data from Wildlands in New England.

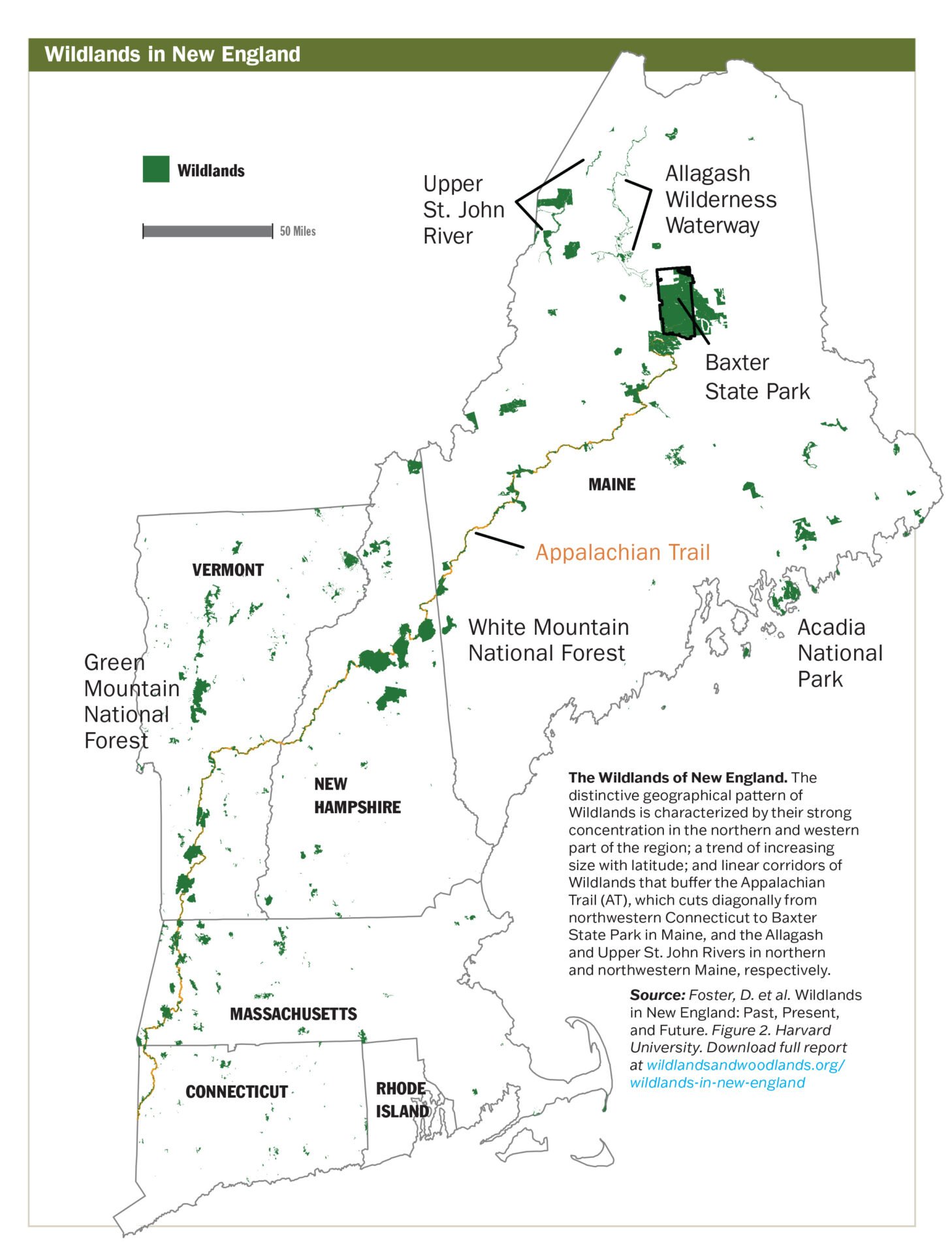

The geographical distribution of wildlands across New England is uneven. WiNE reports:

Wildlands are strongly skewed towards northern, elevated, rural areas lying distant from larger populations.

As a result of this uneven distribution, most wildlands are composed of higher elevation northern hardwoods, spruce-fir, and aspen-birch forests, with significantly smaller areas of oak-hickory and pine forests. Lower elevation northern hardwoods, spruce-fir, and aspen-birch forests, which provide vital wildlife habitat and have the potential to store great amounts of carbon, are also under-represented.

The authors of WiNE concluded there are nowhere near enough Wildlands in New England. To reach Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities’ goal of “at least 10 percent Wildlands, we need a tripling of the current 1.3 million acres.” As the climate and biodiversity crises intensify, I, and many others, believe that science—and our ethical obligations to other species—challenge us to aim much, much higher.

Wildlands in New England. The distinctive geographical pattern of Wildlands is characterized by their strong concentration in the northern and western part of the region; a trend of increasing size with latitude; and linear corridors of Wildlands that buffer the Appalachian Trail (AT), which cuts diagonally from northwestern Connecticut to Baxter State Park in Maine, and the Allagash and Upper St. John Rivers in northern and northwestern Maine, respectively. WiNE Report, p. 10.

Establish A New England Wildlands Network

Wildlands in New England has presented us an excellent road(less) map to develop a New England Wildlands Network, and the narrative to increase already growing public support for accomplishing this work with all due speed. It offers a vision for establishing a Wildlands Network from inner city to the remotest forests on northern New England: “While there is need to establish small local wild areas in strongly humanized landscapes, and integrated complexes of Wildlands, Woodlands, and farmlands across much of southern New England, the 8-million-plus acres of undeveloped and largely uninhabited former paper company lands of northern New England offer an unparalleled opportunity for rewilding vast expanses of land.”

The Report offers the following recommendations:

strengthen the protections of existing Wildlands;

bring the 226 candidate properties that failed to meet all three Wildlands criteria into compliance with the criteria;

assure that new Wildlands meet the three criteria and enjoy strong protection; and

address environmental injustice, especially in urban areas where green spaces are often small or non-existent.

It is a basic human right to live within a 10-15 minute walk of safe, unmanaged green spaces. Many urban green spaces will be relatively small, but will provide essential services even if they fail to meet the three Wildlands criteria. This is one reason the authors of WiNE intentionally refrained from setting a limit on the size of a parcel under consideration for Wildlands designation. Existing and new urban-oriented land trusts can work with municipal governments to turn this dream into reality.

Buy Land: They Don’t Make it Anymore

Land trusts should consider the ecological, economic, and social benefits of forever wild easements. State and Federal land agencies should recapture the spirit of the 1911 Weeks Act that established the eastern national parks and again aggressively acquire lands to be managed for future old growth.

The Northern Forest Lands Study warned in 1990: “The public’s inability to respond to the sale of land that might be suitable for public ownership in a timely fashion . . . means that an important potential owner of the Northern Forest is largely excluded from the market.” The only large addition to the federal land base in New England since 2000 was Katahdin Woods and Waters, which owes its existence to Wildlands Philanthropist Roxanne Quimby, founder of Burt’s Bees.

Compared to the costs of habitat degradation, extinction, and increasing climate calamities, the price of land to stave off the worst impacts of the climate, biodiversity, and human welfare crises is a bargain.